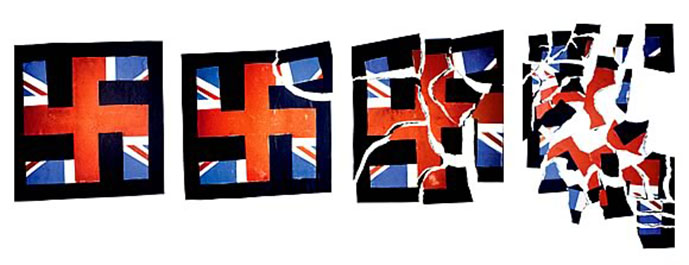

Not long after Conservatives gained power in Great Britain under Margaret Thatcher, Eddie Chambers, a young, black art student, tore a print of the Union Jack into pieces and reassembled it in the shape of a swastika. The result was a powerful--and controversial--statement about what he saw as the appropriation of the country by racist ideologues. In the work, Destruction of the National Front, the Union Jack/swastika occupied the first of four panels. In the other three, Chambers gradually disassembled the image until it became an unrecognizable collection of fragmented colors and shapes. Like the twist of a kaleidoscope that causes an image to blur momentarily before it resolves into a new pattern, Chambers' final panel offered the possibility of transformation.  Destruction of the National Front was a seminal work in what came to be known as the Black Arts Movement in Britain. The movement burst onto the art scene in the 1980s, giving rise to both outrage and admiration, and, in the process, remaking British culture. The movement itself was a response to the social and political currents and tensions of the day and, at the same time, an effort to make the invisible--in Ellisonian terms--visible. There was a sense of urgency as artists "struggled to produce a public and vital black British identity," says Ian Baucom, a professor of English at Duke and an expert in postcolonial studies. He compares the movement in importance to the Harlem Renaissance in the U.S. in the 1920s, the Sophiatown arts movement in South Africa during the 1950s and 1960s, and the early-twentieth-century Celtic Revival in Ireland. Baucom is a co-editor--along with Sonia Boyce, a renowned artist, and David A. Bailey, a photographer and associate senior curator at the Institute of International Visual Arts (inIVA), in London--of a new book, Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain, the first comprehensive look at the British Black Arts Movement. The book, which is co-published by Duke University Press, inIVA, and the African and Asian Visual Artists' Archive, grew out of a series of conferences in England, at Yale University, where Baucom used to teach, and, in 2001, at Duke's John Hope Franklin Center.

In the context of the British Black Arts Movement, black was an expansive and inclusive term that comprised people of Asian and Indian, as well as Caribbean and African, descent--people who came, or whose parents had come, to Britain from the former colonies of the British Empire. To be "black" had resounding political connotations, Baucom observes. " 'Black' in the 1980s was a way of identifying people who had been disenfranchised, as well as making a kind of ethnic and racial mark." The disenfranchisement came in various guises. Under Thatcherism, it was evidenced in the British laws of suspicion, know as "Sus" laws, which allowed the police to arrest people not just for crimes that had been committed, but also for crimes that they suspected might be committed, Baucom says. Black Britons believed that the police used the Sus laws to target, harass, intimidate, and discriminate against nonwhite Britons. In 1981, tensions over the Sus laws and other factors led to the Brixton riots, three days of violence, looting, and burning. An official report published after the fact found that the riots "were caused by serious social and economic problems affecting Britain's inner cities." One of the main causes of the outbreak was "racial disadvantage that is a fact of British life," the report found. Also contributing to the outrage expressed in the riot, and much of the Black Art that followed, was the British Nationality Act of 1981, which sought to define British citizenship in radically circumscribed terms: You were British only if you were descended from an ancestor born in the British Isles. The law abolished "the historic right of common British citizenship enjoyed by the colonial peoples," according to the Sunday Times. "In effect," Baucom wrote in a 1999 book, Out of Place: Englishness, Empire, and the Locations of Identity, "the law thus drew the lines of the nation rather snugly around the boundaries of race."

Too snugly for many Britons, the children of people who emigrated from the colonies in large numbers after World War II. By the mid-Seventies, those children--born in Britain--began reaching early adulthood and found themselves "really having to insist upon the validity of what it means to be black and British," says Baucom. "And out of that kind of generational experience and experience of active disenfranchisement, alienation, and real discrimination, a variety of political movements emerge--particularly young artists who want to represent visually the reality of Britain's multi-racial characteristics, what it means for the body politic to include black bodies, black cultures." The question of how (and whether) to define a "movement" made up of so many threads--people, cultures, experiences--is at the heart of Shades of Black. There are no easy answers. Many of the issues that spawned the movement "are as yet unresolved," British scholar Stuart Hall writes in an essay, one of thirteen contributed by many of the major players in the movement, including artists and curators, as well as scholars. Theirs is a lively--and sometimes contentious--discussion. In the best tradition of scholarly discourse, the essayists debate how to analyze and present the work created by these artists. They examine social, political, cultural, and artistic currents that led to and ran through the movement, even as they disagree over the appropriateness of encapsulating such a diverse group of artists and body of work as a movement.

"We wanted to maintain uncertainty about that," Baucom says. "To listen to artists who wanted to say, 'This is an academic enterprise to classify this movement. There was no movement; these are artists.' " Those artists produced work as varied as Rotimi Fani-Kayode's Sonponnoi (1987), an elegant photographic portrait that celebrates the nude, black masculine form, and Sutapa Biswas' disturbing Housewives with Steak-Knives (1985), which depicts an ordinary Indian woman as Kali, the Hindu goddess of death. One of her four hands clutches the severed head of a white man; another, a bloody meat cleaver. And yet there is common ground, Baucom says, the "sense that it has been a movement to engage, visually, the experiences, the aesthetic richness, and the vibrant cultural life of black Britons in the post-World-War II period." Perhaps more significant, "it is a movement, also, to re-imagine the very contours of 'Britishness,' to expand and refashion understandings of what Britain is and what it will continue to be." "There is a wonderful line in Salman Rushdie's The Satanic Verses: 'The trouble with the English is that their history happened overseas, so they don't know what it means.' In one sense this movement can be understood to emerge when that overseas history came back to England in the person of these artists and they resolved to make themselves, and their histories, so vibrantly visible."

|

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor