In the summer of 2010, Nyuol Tong ’14 returned to his home village of Ayeit in what is now South Sudan for the first time since he was five years old. He saw the remnants of war. Destroyed houses. Scorched land. Scarred people. Scarce jobs. A young population. And no schools. “Not even a single school,” Tong says. “That was a horrifying fact.”

Tong had read many memoirs and heard many testimonies about his home country. Most were stories of suffering, of war, and of trauma. There were the haunting and inspiring tales of “the lost boys”—the 20,000 or so Sudanese children, mostly boys, who fled their families during Sudan’s twenty-two-year-long civil war and lived among themselves, wandering in the wilds or living on the streets—who rose above the odds, with an extraordinary effort, to achieve what others said was impossible.

It takes a village: Construction of Malualdit Liberty Academy put members of the Dinka tribe to work and used mostly local building materials. [SELFSudan]

Tong’s story is not one of those stories, he says, or at least he hopes you don’t see it that way. Where he is now—which is at Duke, as a rising junior majoring in literature and linguistics—and what he is doing now—leading efforts to build a school in his homeland through his nonprofit SELFSudan (the Sudan Education for Liberty Foundation)—is “nothing more than the simple extension of my education and my experience…and the result of many people.”

This is not a story of a lost boy who found his way home. Instead, Tong says, it is a “narrative of gratitude.”

When he was a child, Tong longed to go to school. Born in January 1991 into the Dinka tribe in southern Sudan, he was one of thirty-five children of Lueth, the chief of the village of Ayeit, and his seven wives. Though Lueth was “respected, admired, praised, and elevated” because of his status as the village chief, Tong says, he often talked of his greatest regret—that he did not receive a college education. Tong’s mother, Abuk Thuch, also talked of the importance of being well learned. Tong craved education for himself.

But during Tong’s childhood, Sudan was in the midst of the longest civil war in Africa’s history. After Sudan received its independence from the British in 1956, power had been consolidated in the north, home to a largely Arab and Islamic population. In the south resided a largely African and Christian population that felt disenfranchised. The first of two civil wars had broken out in 1955 between the northern and southern Sudanese. A peace agreement was signed in 1972. But by the end of the decade, oil had been discovered along the border that separated the north and south; and in 1983, Sudanese President Gaafar Nimeiry declared Sudan an Islamic state. The war resumed, and an almost uninterrupted period of fighting occupied the next twenty-two years, leaving nearly 2 million dead, more than 4 million displaced, and up to 80 percent of the villages and rural areas destroyed.

Summer 2010: Tong returns to his home village in Sudan for the first time since he was five years old and is reunited with his father. Village leaders agree to enter into a partnership with SELFSudan to bring the first school to the village. [SELFSudan]

Because Lueth was a village chief who had influence over the community, a rogue militia group affiliated with the Islamic government in Khartoum solicited his help to fight against the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army and other factions supporting southern Sudan. After Lueth refused to join a Khartoum-backed militia, the militia captured him. He escaped and went into hiding. When the militia could not find him, they tried to intimidate him by targeting everything associated with him. They torched the family’s land; they stole the family’s cows, prized possessions in the Dinka tribe; and they targeted his children, including Tong. Once, armed men from the militia grabbed him, threw him into a hole, and fired ammunition around him. After that, his mother, several brothers and sisters, and Tong fled to Khartoum, the capital of Sudan. Tong was five years old. He would not see his father for the next fourteen years.

In Khartoum, a highway divided the city in two. One side was home to Arabs and brick houses; the other to Africans and cardboard shacks, where Tong and his family lived as refugees for the next four years.

Tong built a reputation as a good soccer player, and the children in the Arab neighborhoods often asked him to cross the highway and join their team for pickup games. “I crossed that highway many times, and never thought much of it,” he says.

Oftentimes, after a game, on his way home, Tong saw the imam in charge of the local mosque sitting on a chair outdoors, wearing glasses, and reading a newspaper. “It was the most inspiring image,” Tong says. Sometimes Tong would stop, grab a chair, sit beside the imam, and pretend he was reading the paper, too. Tong couldn’t read, so the imam would tell him what was going on in the country and explain words in the daily news, like economy and geography. “That’s what I wanted to be— to be reading a newspaper and to be as cool as that man,” Tong says. “I just wanted to be educated.”

Tong struck up a friendship with the imam’s young son, Bashir, who attended a public school in the Arab-controlled area. Tong peppered Bashir with questions about his school work, asking him how to conjugate verbs and explain lessons. Bashir answered every one; he gave Tong whatever textbooks he had from the previous grades; and he taught him the national anthem and verses from the Koran. One day, when Tong was nine years old, Bashir told him he could come to school with him. “The school is public and free,” Bashir said. “All you need is a school uniform.”

Tong was ecstatic. For the next year, he babysat, delivered meals, washed cars, washed dishes, and swept the street to earn money to purchase a school uniform and supplies. Once he had enough money, he told Bashir, “I have everything in place.”

On his first day of school, Tong arrived at 7:30 a.m. and was greeted by the Muslim boys he had become friends with through soccer. During the morning assembly, they sang the national anthem and read verses from the Koran together. But before Tong could make it to the classroom, the headmaster stopped him and took him to the front office. ”You can’t go to school,” the headmaster told him.

“Why?” Tong asked.

Without looking him in the eye, and before ushering him off the school grounds, the headmaster said, “You just can’t go here.”

Tong ran to a spot near a tributary of the Nile River and burned his school uniform and supplies. “It was the most painful experience of my life,” he says. “It was the first time I realized that the highway was a dividing line and that Bashir and I lived in two different worlds. My self-esteem burned with the school uniform and supplies.”

Tong became “bitter, rude, and violent,” he says. During the pickup soccer games, he would instigate fights with other players or just stand in the middle of the soccer field and not move. Sometimes when the ball came to him, he would poke holes in it with sharp metals, nails, and sometimes knives.

One evening, he was drawing graffiti on a neighborhood wall when a student at the University of Sudan named Vivianna Francis spotted him. She thought his drawing— a depiction of Sudanese singer Mustafa Ahmed—was spot on. Though her father was a member of the ruling National Congress Party, Francis supported the South Sudanese cause and invited Tong to attend a new school for refugee children that she and some friends were starting. He attended for four months before government officials shut it down because they said it was associated with rebels. “I felt defeated again,” Tong says.

Francis continued to work with him one-on-one. She took him to the National Museum of Sudan, where he first learned about the history of the country. She introduced him to literature and history books. And she helped him turn his frustrations into poetry. At a Christmas party for the refugee community, he recited a poem that she helped him write. “Why does this happen?/ How can it happen?/ The nameless, faceless, homeless/ With no place to call home,” he recalls reciting. The words moved other refugees to tears.

Over the next several days, everywhere he went, people asked him to recite the poem again—and again they’d cry. When he showed up at the soccer field in his own neighborhood for the first time after reciting the poem to the refugee community, the other South Sudanese kids applauded him. “That is when I realized that I had so much more than school— that I had a community of my own and that I mattered,” Tong says. “I want every kid to feel like they have something that matters.”

A few years later, Tong learned that Vivianna Francis had gotten married and begun to work at a bank. Bashir had dropped out of school to make money. “Quite upsetting,” Tong says. So when he finally had the chance to attend a formal school, Tong didn’t waste the opportunity.

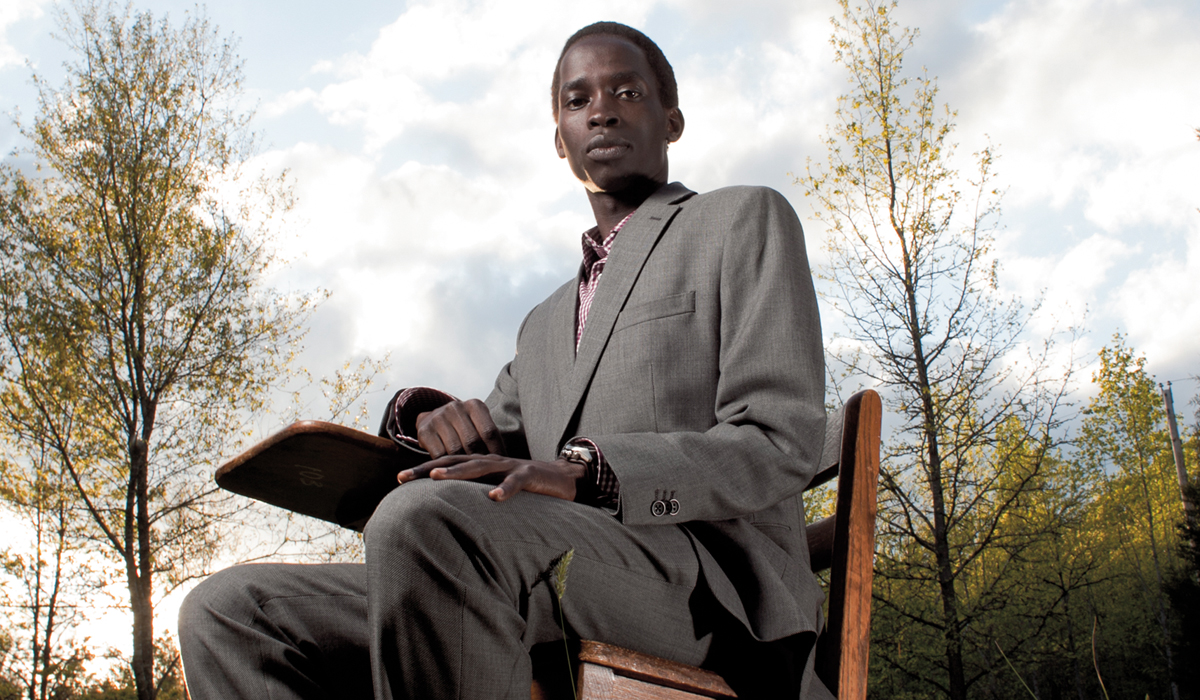

Fall 2010: Tong enrolls at Duke as a Reginaldo Howard Memorial Scholar. [Megan Morr]

He came to the U.S. when he was fifteen years old on a scholarship to attend the Dunn School, a small college preparatory school near Santa Barbara, California. Again, his life had taken an unexpected and fortuitous turn. In 2003, his family had left Khartoum for Egypt, where the United Nations had an outpost that helped refugees migrate to the West. In Cairo, he took a writing workshop for refugee children taught by Brooke Comer, an instructor at the American University in Cairo. Comer befriended Tong and recommended him to Dunn, her alma mater.

Tong had little experience with English, and at first he struggled at the Dunn School. An academic adviser worked with him before and after school and encouraged him to write poetry in the language. Tong also took introductory courses in algebra and geometry in the same semester his freshman year to catch up with his peers. “He had such a sincere passion for learning, and he absorbed everything,” says Helena Avery, who taught Tong geometry at the Dunn School. “He had this air about him: ‘Teach me! Teach me!’ ”

Tong caught up quickly. By his sophomore year, he had started a philosophy club at Dunn. A Catholic priest in Egypt had introduced him to philosophy, loaning him books written by Friedrich Nietzsche and other philosophers and theologians. Through the readings, Tong came to fall in love with the subject. He viewed it as a way of life, he says. He imagined philosophy as a tool that would help people deal with difficulties, to see beyond their own experiences, and to confront the damaged world that they live in.

Yet while he loved the education and the experience he was receiving in the U.S., Tong also felt guilty. Here he was in a wealthy American city, enjoying white chocolate mocha and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. There were paved roads and efficient means of transportation. America was a place where “distance is defeated” and “time is humbled,” he says. He had his dream. He was in school. But he missed singing to the cows, the closeness to nature, the thoughts of the sun. “There is nothing as painful as having something here,” he says, “and knowing people back home don’t have it.”

“There is nothing as painful as having something here, and knowing people back home don’t have it.”

With members of the Philosophy Club, Tong talked about the tension he felt, what he called his own “education crisis.” “I’m trying to reconcile my privilege here in America with the hardships back in Sudan,” he had said. His friends told him they all should do something to help. Members in the club looked deeper into the history of the country and the conflict. Although a new peace agreement was signed in 2005, Sudan was ravaged by its long war. Millions remained displaced, and the fighting over resources continued, including among the tribes in southern Sudan. In 2011, the southern region gained independence, becoming the nation of South Sudan. But an estimated 80 percent of the new country’s population was illiterate.

Tong, meanwhile, continued to wrestle with a way to bridge his past with his present. He ultimately ended up wanting for Sudan what he had always wanted for himself: education. “We need education to give us the tools to confront the trauma of the almost half a century of horrors and hardships, and to create a drama that inspires us and that helps us overcome the trauma to build a better world,” he says.

From the school Philosophy Club in 2008 sprang the nonprofit SELFSudan. Tong, its founder, was seventeen years old.

With the help of Dunn teachers such as Avery, Tong and other students developed a vision, a strategy, and a plan to raise awareness for the nonprofit and the conditions in Sudan. By his junior year of high school, Tong was traveling around the country to speak about life as a refugee and the need for education in southern Sudan. One of those speaking engagements was at the Duke Islamic Studies Center, which introduced him to Duke and ultimately led him to enroll at the university.

While pursuing his studies at Duke, where he is a Reginaldo Howard Memorial Scholar, Tong continues to raise funds through events and letter-writing campaigns. SELFSudan has now raised more than $40,000 for the construction of schools.

After he finishes his degree, he plans to pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy. But if all goes according to plan, students in Ayeit will be opening their books in a newly built school long before then. “It is my belief that education is the only tool of which Sudan will be liberated from war,” he says.

Tong carried this message with him when he returned to his home village in 2010 and was reunited with his father. Lueth, still the village chief, helped his son organize a series of meetings with community leaders.

Though the Dinka tribe was considered to be “a headstrong culture resistant to change,” Tong says, the village leaders seemed ready for change, and they certainly wanted a school. They agreed to give SELFSudan land—and not just any land, but the land where the village’s collectively owned cattle camp sits, the most sacred land in the village.

“That gave me the sense of the gravity of the matter and how big of a need a school is and how committed the community was,” Tong says.

But Tong didn’t want SELFSudan just to raise money and put up a building. Other organizations have tried building schools in undeveloped areas, with notably mixed results. In 2011, for example, CBS’ 60 Minutes alleged that the Central Asia Institute— the organization that Greg Mortenson, author of the best sellers Three Cups of Tea and Stones into Schools, cofounded to build schools in Pakistan and Afghanistan—mismanaged millions of dollars of donations, leaving many schools abandoned or used for other purposes—or never built at all.

But Tong says the venture between SELFSudan and Ayeit is different because it is based on true partnership. Tong and village leaders agreed that SELFSudan wouldn’t aim for its presence in Ayeit to be sustainable; instead, the nonprofit would work to be dispensable. “This means we build on the community’s proven capacity and potential, and we only provide what is needed,” Tong says.

Under the “dispensable” plan, SELFSudan is providing the initial capital costs to build a school facility, which will comprise eight classrooms, a library, and teachers’ offices. The nonprofit will train the teachers, equip the facilities, and develop a curriculum. And to oversee construction and manage its operations in South Sudan, SELFSudan hired three teachers, including two former headmasters, who had fled Ayeit during the war but returned to work for the nonprofit. But the village would own the school; and after six years from the school’s opening date, SELFSudan would be completely out of the picture and the village would single-handedly operate the school.

To create jobs and pump money into the local economy, SELFSudan agreed to buy nearly all of the brick and other construction materials from people within the village. Village leaders also pledged that they and other community members would sell cows to establish a Community Development Fund. This fund would give community members loans to start businesses or subsidiary projects such as a collective farm, a grocery store, or a graingrinding store, which would generate funds for the school. “This signaled to me [they were ready] to transition from dependence on cows for livelihood to dependence on education,” Tong says.

Not everyone was so convinced. When Tong met with education officials of his home state Warrap, they told him his plan wouldn’t work. They said a culture of dependence had been created during the decades of war, and people expected non-governmental organizations to do everything. If you don’t work with an NGO, they warned, you’re not going to get the support you need.

“So in a sense,” Tong says today, “I’m trying to prove the education officials wrong.”

When Tong was growing up, his mother told him “grand stories” about his life to help him “rise above the realities of the present condition,” he says. When Tong longed for a better life—with no school to attend, his homeland torn by war, his father in hiding, and his family cast out in the slums of Khartoum—his mother told him he was a prince and that his stays in the refugee camps were just temporary stops. “You’ve got a palace waiting for you,” she often told him.

And so he does. Construction on SELFSudan’s first school, the Malualdit Ayeit Liberty Academy, began last summer. Though peace remains tenuous, Tong will return to South Sudan this summer to open it, with classes beginning in the fall. It’ll have an enrollment of seventy students. Leaders from seventeen other villages have already contacted Tong and expressed interest in joining with SELFSudan to build schools in their own communities.

“I am the sum of many people. The Dunn School, Vivianna, Bashir—these people are all my creators,” Tong says. “The school itself is not an obligation but an extension of that shared support and expectation and encouragement and faith….”

“And if you can conceive of a way to change the world, why not try? Anyone can at least try.”

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor