In the spring of 2020, JaBria Bishop built her first video game.

It was a 2D side-scroller—think Super Mario Brothers—which she believes she called Lunar Dreamscape. In it, a little girl wakes up in a lost world. Bishop’s idea for this whimsical game was for the players, too, to feel lost, so she designed it accordingly.

“I wanted the player to also feel how the little girl feels,” she says.

Bishop—today a senior; then a junior—was a student in Asian and Middle Eastern Studies department chair Shai Ginsburg and professor Leo Ching’s “Games and Culture” course. Her project communicated one of the class’s key takeaways: The mechanics of a game (how the controls work; how the character interacts with its world; what the player can and can’t do) serve the same function as, say, meter in poetry or key and tempo in music. She had learned to view games analytically and understand the emotional and conceptual underpinning of something as seemingly innocuous as a video-game character’s abilities.

Indeed, gaming permeates the lives of the middle and upper classes globally, Ginsberg says, but the meaning, the function of our video and tabletop gaming habits is rarely addressed in depth. In short, play isn’t taken seriously. The European Protestant conceit, Ginsburg continues, maintains that work and play are a binary, yet he and Ching reject this dichotomy. “Games and Culture” parses gaming with the same rigor with which one would study literature or film. It’s also structured like a role-playing game (RPG), with the syllabus outlining multiple “quests” rather than a single, shared set of assignments. Coursework, too, involves playing a lot of video and board games.

In Ginsburg and Ching’s course, the subject is the method.

“We hear a lot of professors talk about these alternative ways of pedagogy and blah blah blah, but oftentimes, those are done in an abstract way,” says Ching (whose first favorite video game was Space Invaders). “For us, playing board games with the student actually concretizes some of this sense of equality.”

Indeed, when the dice are out, when the pieces are on the board, and when the cards are dealt, there are no instructors and students—just players. Ginsburg (who loved Legos from an early age) compares it to siblings playing together: The age difference disappears. Especially when the class plays a new-to-everyone game together, all are novices and there’s a momentary suspension of the teacher-student hierarchy. This is by design.

The course is just like a game, says Ching. “Sometimes when you play it, a game is designed in such a way that at least gives you a sense of agency, even though you might not have it. You feel like you’re doing something because the game allows that interactivity.”

Ching grew up in Japan and Taiwan, where the education system privileged rote learning. After that upbringing, he found the participation and discussion within American education particularly stimulating. Yet he and Ginsburg believe students can be offered yet more active roles in their schooling; that the teacher-student hierarchy can be at least paused, allowing students to co-create the course.

“It’s like if we talk about community theater,” Ching offers.

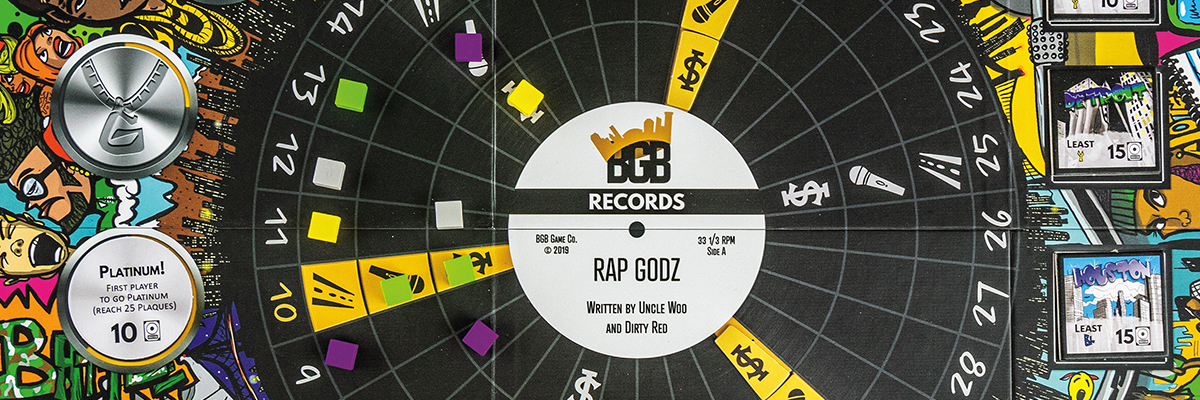

In the course he, Ginsburg, and each semester’s students co-create, their play includes an unpacking of games’ social context and subtext. Some of this is overt, such as gaming’s troubling history of representation. Statistically, Ginsburg says, you’re more likely to see a sheep on a game box than a woman, while nonwhite and LGBTQ characters are even rarer. Ching and Ginsburg include modern games that consciously buck this trend, such as Omari Akil’s Rap Godz.

As a Black man, Akil is rare among board or video-game designers. Accordingly, representation is expressed through mechanics, too. Most game designers are white males and most game characters are white American males, Ginsburg says. They’re aggressive and assertive, and gameplay is defined by competition, conflict, and the pursuit of a goal. The feminist critique, Ching says, holds that this is a heteronormative, masculine game design.

“This seemingly very democratic, open-ended, fun space” is actually informed by a chauvinistic white privilege “that we have to undo,” adds Ginsburg. “We have to unpack this facade of inclusion and fun.”

It’s heavy conceptual lifting, implying deep philosophical questions. What, Ginsburg wonders, does game design communicate to an international audience about American culture? About Korean culture? About Japanese culture? And would, Ching wonders, broader representation in game design result in different definitions of game? In games with no goal? In collaborative games?

In their course, such lofty hypotheticals and sociocultural analyses are explored through play.

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor