When, back in 1995, Tallman Trask III was emerging as the likely choice as Duke’s executive vice president, law professor James Cox was chairing the search committee. He did what search-committee chairs typically do: He called an administrator at the University of Washington, where Trask was then working, to check him out.

The conversation didn’t start on a typical note. “There was a pause. Then all of a sudden, there was this sigh,” Cox recalls. A long sigh. And a personal observation: “He plants flowers.”

Where is this conversation going? Cox wondered. But the administrator went on: “One of the first things I noticed when Tallman came on board is how beautiful the campus suddenly became. He planted flowers. Over his tenure here, I just realized, God put us on the world for some special purpose. And Tallman was put on this planet to make universities better.”

Cox makes a sweeping gesture to take in his lawschool surroundings. Construction that, over the years, has overtaken the school’s original featureless façade of red brick. Just out of view, a glass-enclosed oasis for eating and conversation. A stand of trees that’s been preserved through all the physical growth. “When I look out my window now, the scene is a lot more beautiful than it was before Tallman came.”

Trask retires at the end of the calendar year, a halfyear later than originally anticipated. Vincent E. Price, the third Duke president Trask has worked for, says it became clear that the timing of the transition had to be adjusted: “When the pandemic hit, we had the benefit of an experienced executive-leadership team to navigate the university through unchartered waters. It was important to keep that team together.”

Duke is looking to its centennial in 2024. And it’s striking, says Price, that Trask has been a major presence at Duke—really a major shaper of Duke, and not without controversy—for a quarter of that time. It’s quite a portfolio: finances, campus planning, real estate, human resources, information technology, stores, maintenance and construction, safety and security, parking and transportation.

His manner can seem gruff, but it can also seem refreshingly direct. In any case, it’s brought results, right from the beginning. He talks about how Student Affairs was initially in his area. “The argument made to me was, ‘Well, students are in the dorms, the dorms are buildings, and that’s what you do.’ Well, that’s just weird.” So a trade ensued. Student Affairs went to the provost, the academic side of the campus. Information technology had been in the domain of the provost. That was weird, too, he argued. It became part of his portfolio.

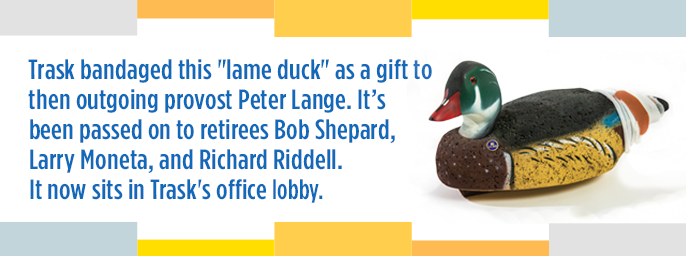

One of the first things you notice as you walk into Trask’s office, on the second floor of the Allen Building, is a message, taped to the door, from a Panda Express fortune cookie: “You are a charmer.” On his desk he has a big red button; when you hit it, a mechanical voice calls out, “No!” His longtime assistant, Nancy Metzloff, has a corresponding big green button: “Yes!” Now and again, they engage in a cacophonous back-and-forth.

If Trask doesn’t feel he needs to be a conventional charmer, he’s happy to express his own sense of style. Beyond the pocket squares with matching socks, there are the madras jackets, the rainbow-colored Nike sneakers. ”My sartorial sense is purely Pasadena,” says the native Californian. “I’ve dressed that way more or less since I was in high school.”

His office shelves are packed with books on design and architecture. Some showcase star architects like Frank Gehry and Cesar Pelli; there are also Trees and Shrubs; The Stones of Naples; The Campus as a Work of Art; Scandinavian Design; American Gargoyles. (There are also nods to more mundane aspects of campus planning, like The High Cost of Free Parking.) On his desk, you can spot a standard computer and a not-so-standard screensaver. It rotates between the image of a 1973 Porsche, the very first Trask-owned Porsche, and Porsche portrayals through the years—an attachment inherited from Trask’s sports-car-driving father.

Trask arrived at Duke three years into the presidency of Nannerl O. Keohane. Cox recalls it as “the search from hell”; it stretched over two years. For his part, Trask says, “If you would have asked me six months before I decided to move to Duke, ‘What are the odds you would move to North Carolina?’ I would have said, ‘Can odds be less than zero?’ It just wasn’t on my radar.” But the University of Washington soon was in the midst of a messy presidential transition. So he adjusted his expectations.

Having graduated from Occidental College, Trask had earned an M.B.A. from Northwestern and finished a Ph.D. at the University of California, Los Angeles. His doctoral dissertation was “Student Perceptions of College Administrations.” It’s filled with data sets, mathematical modeling, and statistics-driven concepts like “correlational matrixes.” He applied all those tools in exploring university culture. Universities with top-down governance, he found, tend to rate lower on “institutional quality measures.” He pondered a cause-and-effect quandary: “Does the low-quality factor induce an environment which can be operated only with a firm hand, or do more restrictive administrative styles hold back the academic development of the institution?”

Keohane had a firm sense of her own administrative style, but at the time she recruited Trask, she was still building a team of top administrators. She found in Trask someone who understood higher education from his own experience, and from having studied it. “I figured that he would be the kind of executive vice president who would fit well with the academic side—would fully understand it, but not try to manage it. And that’s exactly what happened.”

Trask had been in charge of academic and administrative computing at UCLA, as vice chancellor for academic administration, when he was in his mid-thirties. Duke’s IT past and present are wrapped together in another of his office displays. It’s a bundle of data-carrying wires recovered in the midst of a library renovation; those wires would have carried data under protocols now considered exceedingly slow (kilobits per second, not the current gigabits per second). He says, “We got it right, and we got it right early. Unlike other places, we didn’t have eight-figure failures in the process. Now we’ve got the infrastructure everybody else wishes they had. And we run it across the entire enterprise, including the School of Medicine and the three hospitals, which nobody else does.”

Part of what energizes Trask, says President Price, is the chance to build systems—from information technology to payroll. “I think he finds them as interesting and challenging to envision and construct as a new building would be to envision and construct. It’s satisfying for him to contemplate a building when it’s up and running. He gets the same satisfaction from an administrative system when it’s up and running.”

Trask’s role of overseeing finances has coincided with economic upswings and downturns—none more dramatic than the pandemic. Duke announced a series of cost-saving measures: expenditures above $2,500 requiring approval from the top of the hierarchy; a hiring freeze except for positions deemed essential; no salary increases for all those earning more than $50,000; no university-paid retirement contributions for a year; temporary salary reductions for highly paid staff; a pause in new construction projects.

To Trask, this all feels different from the earlier moment of financial stress, which came with the Great Recession in 2008-09. Back then, the most worrisome hit applied to the endowment. But endowment performance over a single year or so wasn’t bound to affect university spending levels all that much: The payout policy takes into account the returns over several years, and so is designed to smooth the effect of market fluctuations. It was just a matter of waiting out the markets as they recovered. Now, though, the revenue hits persist, with no clear endpoint for losses in dining, housing, stores, parking, and elsewhere.

In the end, Duke “will have to be a little bit smaller,” Trask says. “But 99 percent of colleges and universities would be happy to have Duke’s problems. Their problems are a lot worse.”

A pandemic hardly figured in the scenarios imagined for higher education. But Duke’s president during the Great Recession, Richard H. Brodhead, says Trask at the time “saw what was coming, if not necessarily on the scale it would take. Because of that, we weren’t as far out over our skis as some universities were. Tallman took the message that there were reasons for caution.”

At the same time, Brodhead, Trask, provost Peter Lange, and the rest of the leadership resolved not to put an absolute stop to faculty hiring. The idea, Brodhead says, was to avoid Duke’s sinking into “an intellectual ice age.” Duke, then, put itself in the position of attracting faculty talent when virtually no one else was hiring.

Lange, who was provost from 1999 until 2014, says that period of financial stress highlighted Trask’s buying into the spirit—not necessarily commonplace in higher education—of “collegiality and mutual trust.” Early in his provostship, he recalls, Trask talked about his job as delivering the maximum resources to the academic sector, consistent with his fiduciary responsibilities. “I don’t know how many executive vice presidents think that, much less being willing to say that,” Lange adds. “It’s so important.”

That was important for Keohane as well; in her view, one priority for the position was building trust with the faculty over financial decisions. “I wanted an EVP who would be respected enough by the faculty to be listened to, and, equally important, who would be ready to open the books. And that’s basically what Tallman said: ‘Look, whatever you want to find out, come and I’ll show you. It’s all open.’ ”

From the faculty perspective, Cox agrees that the atmosphere changed. In the early 2000s, he led a faculty advisory committee on university priorities. “There were concerns at the time about the budget for athletics, about how that impacted the rest of the university. I walked in to tell Tallman about those concerns. He said, ‘I’ve been expecting you. Here are the financial statements for the past three years.’ He knew he could trust us. And we certainly trusted him. He was always straight with us.” During Keohane’s administration and beyond, it wasn’t just the atmosphere that changed; so, too, did the physical campus. Trask had “so many opportunities to build new buildings or to renovate old buildings,” Keohane says. “That was a period at Duke when there was a lot to be done.”

More than being a builder, Trask had “a strategic sense of the campus,” as Keohane puts it. She had had little exposure to the campus before being interviewed for the Duke presidency; her first impression was that the layout was confusing. “I was thinking, why is the campus arranged this way? And, of course, it was just that it had grown up that way. Tallman immediately saw the importance of Duke as a cohesive and coordinated architectural entity.”

Lange, the longtime provost, says the eventual campus plan meshed aesthetic and educational interests. “Duke isn’t land-poor, so there was the temptation to keep spreading the campus footprint wider and wider. But Tallman had a different architectural vision. And it fit perfectly with the strategic vision on my part. That is, we were going to be more interdisciplinary, and we needed to get faculty members working together in close proximity.”

A new engineering building, for example, would go up in a former parking lot—“infilling,” as Lange describes it, in a way that promoted both the sense of a unified campus and the capacity to collaborate. Keohane’s successor as president, Brodhead, says, “There may be executive vice presidents who are three-quarters as smart as Tallman. But I don’t know of one who has his comprehensive interest in all aspects of a university, particularly its architecture.”

“When I got here, I invited a group of about ten really serious architects to come just hang out for a week,” Trask recalls. “I would walk around with them and say, ‘What do you think? What would you do here? It was a really interesting experience. We ended up hiring about half of them.”

A family trip from his childhood days had sparked Trask’s attachment to buildings. It was to visit Sea Ranch, along the northern California coast, which is a showpiece of modernist architecture and environmentally conscious landscape design. In his foreword to Duke University: The Campus Guide, published a few years ago, a theme is “place signifies.” He writes: “While at the outset many Northerners argued that the South could never spawn a truly great university, today others suggest that Duke in fact became a great university in part because it looked like one from the start (including artificially worn stair treads).”

Clearly Trask sees a model of sorts in J.B. Duke. The founding visionary, Trask notes in the foreword, spent not just a considerable fortune but also a lot of time on the original plans, “worrying about everything from architectural detail and landscaping to whether there should be ‘less of the yellow and gold color’ in the stone mix.”

To Trask, the university’s history is something not just to understand but also to preserve and to project into the present day. He keeps elements of that history within reach. Price, the president, describes him as “a collector of experiences and historical moments”; he notes that Trask was an undergraduate history major and thought about studying history as a graduate student.

An office visitor will notice a brick from the original Trinity College campus in Trinity, North Carolina. Nearby is an ornament made from a white oak on campus that tumbled after some eighty years. Then there’s a slab that Trask describes as “the next piece that was going to fall out of the ceiling of the chapel”—the original chapel, that is, pre-renovation.

A (Gothic) stone’s throw from the chapel, a projected wing of the divinity school, unveiled in 2005, had been labeled a “sensitive site” by the board of trustees, says Greg Jones M.Div. ’85, Ph.D. ‘88, dean (then and now) of the divinity school. Among the challenges: The “Duke Stone,” captured from the university-owned quarry, needed to be hand-chiseled and blended for the right color effect. “We did an interesting extra exercise with three groups of stone masons building ‘mock walls’ to be sure that the Duke Stone facing Duke Chapel would match well with the style of Duke Chapel,” says Jones. To be faithful to the Gothic inspiration, workers crafted other features out of limestone—complex arches, buttresses, rose windows. “The finials on the top of the building required molds and 280 personhours per finial to be sure they matched the original ones on the walkway between the Gray Building and Duke Chapel,” Jones says. “Tallman paid great attention to those sorts of details, and the building is more beautiful as a result.”

Baldwin Auditorium, renovated in 2013, is one of Trask’s favorites—“a lot of bang for the buck,” in his words. It’s commemorated in his office by a couple of soda bottles, evidently discarded by the auditorium’s original construction crew and recovered during the renovation. “It was, like, the worst space on campus,” he says. “Now it’s this magical space.”

Baldwin is a testimonial to Trask’s power of persuasion: He was determined to land Norman Pfeiffer as the architect; Pfeiffer, with whom Trask had worked back in Washington, had experience in historic renovation (Stanford’s Memorial Church, L.A.’s Griffith Park Observatory), along with a record of designing performing-arts centers in Washington, Colorado, California, Oregon, and at Notre Dame. Pfeiffer at first refused—he was too busy. But Trask wore him down, and he eventually agreed to the Duke project.

Even with his architect of choice on the job, Trask delved into some of the details, notably selecting the materials for the seats: “I knew that would make the room. And I wanted it done in a particular way.”

A bigger project, finished in 2016, was reimagining the original West Union (now the Brodhead Center) to accommodate a complex dining program, complete with dining balconies, lounges, and meeting rooms. Trask says a big challenge was inviting light into the neo-Gothic hulk: “The only way to make that happen was to blow up the back of the building and rebuild it out of glass.” While it’s not an iconic Duke building in its shape or materials, it pays homage to its heritage through features like the color pattern: The glass curtain walls, along with the terra cotta wings, acknowledge the blacks and tans in the stones that formed the original building.

There the architect was the British-based Grimshaw, which had done little work in the U.S. Among all the items displayed in his office, one of Trask’s favorites is an award from the Royal Institute of British Architects. The institute singled out the Brodhead Center as the best building designed by a British architect and built outside Britain. But the process for something so complex wasn’t without its bumps. In conversations with the architect, “I tried to explain to them the vision we had, what we were trying to do,” Trask recalls. “They came back with a design. I remember calling up their principal and saying, ‘I’ve looked at your design. The trustees have looked at your design. We all hate it. So here’s the deal. You’ve got sixty days to come back with something that we don’t hate, or else we’re going to hire somebody else.’

“And they responded. They responded with what I think is a very interesting project.”

As a campus planner, Trask talks about “establishing a pattern” and “not just doing one-offs.” The main quad “was built as one thing between 1928 and 1932,” he says. “There’s nothing else like it in America. And it’s actually worth preserving and recognizing.

“But after World War II, Duke came to the view that nobody knew how to design and build buildings like this anymore. And so, they would have to do something different. To them, different was, ‘Well, we have red-brick buildings on East Campus. Why don’t we build red-brick buildings? And if we leave enough trees between them and the real campus, nobody will know the difference. That’s where Science Drive came from. You have this street with an accumulation of red-brick buildings that look like Midwestern high schools, plopped down because they were quick, utilitarian, and cheap.”

A Trask task, then, was to figure out how to make “Duke-like” buildings. (He says, wryly, that Duke benefits from not having a school of architecture, which would inevitably apply pressure to build with celebrity architects; he compares one building at a peer campus, the product of a so-called “starchitect,” to the movie set for The Cat in the Hat.) “It’s really a few simple things. I mean, it’s scale: They’re largely vertical, not horizontal. They have towers. You can’t say, ‘Well, let’s make them all alike.’ But you can try to have some commonality.”

One expression of commonality is so-called Duke Brick, which, from a few hundred yards away, gives the visual impression of stone. Duke Brick comes in various formulations, which shift from building project to building project—for example, the “Five-Color Brick Blend,” found on the Wilson Recreation Center and consisting of “Brown Tweed,” “Cimarron,” “Brown Irontone,” “Light Autumn,” and “Driftwood Modular Blended Brick,” all in prescribed percentages.

Even as he was building out Duke’s core campus, Trask was extending Duke into the Durham community. For President Price, that part of his legacy points to Trask’s effectiveness as a skilled deal-maker: “Tallman has the ability to bring lots of different parties to the table and to get results.”

Bill Bell can speak to those results; he was elected mayor of Durham in 2001, and was re-elected seven more times. Bell credits Trask in particular for spurring the university’s investment in the Durham Performing Arts Center (DPAC), opened in 2008.

The city lacked the funds to proceed with what would become a gleaming symbol of, and a major force for, Durham’s resurgence. Duke, with Trask as lead negotiator, ended up contributing about $7.5 million to the $48 million project. In exchange, the city agreed that one component would be performances by the American Dance Festival. For decades, the ADF, for its summer season, had based itself at Duke—which itself lacked dance-friendly performance space. Trask realized that a stage suitable for a Broadway production is big enough for dance; the ADF dedicated its 2010 season to him.

Bell also points to an adjoining and earlier project, the American Tobacco campus, redeveloped in 2004. Once a cigarette- manufacturing hub, it became a sprawling sign of downtown decay. “In the 1970s, ’80s, and early ’90s, once-thriving businesses in Durham just walked out,” Trask says. “And back in the 1890s and early twentieth century, industrialists in Durham had gotten themselves into an architecture contest—‘My warehouse is better than your warehouse.’ So what was left was a million square feet of really interesting abandoned buildings.”

American Tobacco was the brainchild of Jim Goodmon, now CEO and board chair for Capitol Broadcasting Company. (He was a Duke student in the early 1960s before leaving to join the Navy.) Goodmon had taken ownership of the Durham Bulls and looked to a new, city-built stadium, right next to American Tobacco, as a springboard for Durham development.

“As we worked more and more, the vision got larger and better, and Tallman was a big part of that,” Goodmon says. “If you ask him what he thinks, he’ll sure tell you. But he never had the attitude, ‘I’m your largest tenant, and I’m going to tell you what I want you to do.’ Instead, it was, ‘I’ve got some ideas, or I know some good architects, or let me help you contact some possible tenants. He has lots of contacts.”

“American Tobacco opened up everybody’s eyes,” Goodmon says. “It changed attitudes about what’s possible in Durham. It changed Durham’s attitudes about itself.”

Duke sometimes has had a rough ride in the Durham community. A reminder of that came in the spring of 2019, when the long-discussed Durham-Orange County Light Rail project went off the rails. The local alternative weekly, along with several local leaders, accused the university of acting in bad faith by encouraging the planning process and then precipitously withdrawing its support. Trask was singled out as the bad guy.

Trask describes himself as a mass-transit proponent. But that project “was flawed in so many ways,” he says. One issue was possible electromagnetic interference with sensitive medical equipment along a portion of the proposed route, next to Duke’s medical center. Another was a design process that kept getting more and more expensive. Originally the state was expected to kick in 25 percent of the overall cost; eventually, the figure was closer to 7 percent. A single change in the proposed route, which involved tunneling and elevating a portion of the line in downtown Durham, would have required another $8 million.

According to Trask, Duke’s objections were clear from the outset, and though various partners pledged to resolve them, the problems remained year after year. The university’s ultimate stance should have been no surprise, he says. “There’s a lot of revisionist history. But there were plenty of problems in the planning that remained problems two decades later.”

Trask’s colleague around Duke’s expanded footprint in Durham is Scott Selig M.B.A. ’92, associate vice president for capital assets and real estate. Selig had worked for Trask at the University of Washington, where he had negotiated the purchases of warehouse properties for a new branch campus in Tacoma. Duke, including its health system, now occupies more than 4 million square feet of space off campus, including about 1.2 million square feet in downtown Durham.

Since their time in Washington, Trask and Selig’s approach has been refined: In Durham, Duke leases all of its commercial space. Universities, which are tax-exempt, typically buy nearby properties, a good deal for a space-constrained campus but complicated for the community. Duke’s leasing rather than buying means that those buildings are generating tax revenue. Duke also serves as a redevelopment catalyst: With Duke as a lead tenant, the developer can borrow more money from banks (which are reassured by the university’s credit-worthiness), and so those developers can think more expansively.

“For any development to work, it takes three things,” says Selig. “Vision, guts, and money. Most people have two of those three. They’ll have the vision and the guts, but they don’t have any money. Or they’ll have the vision and the money, but they can’t pull the trigger.” With Duke resources behind him, “Tallman has all three.”

Pre-pandemic, Duke had about 4,000 employees downtown. As for the economic impact: “Four thousand people from Duke, if they go to lunch once a week, means 800 people going to lunch every single day—forty restaurants with an additional twenty paying customers.” That was then. And looking ahead? Selig imagines that Durham office space will continue to be in demand, but that in many cases, it will be reconfigured: Maybe there will be fewer office workers at any given time, but those workers will want spaces that don’t feel crowded.

His work in spurring the growth of Durham, his colleagues say, highlights one side of Trask: his interest in the various measures of social equity. President Price recalls Trask referring to his time as an Eagle Scout. Trask, in Price’s words, “has been wedded to those renowned Eagle Scout virtues,” service to the community among them.

Because of his commitment to community-building, Trask had difficulty enduring a time of particularly sharp public criticism. Before a home football game in 2014, he got into a disagreement with a parking attendant about access to a road. During the dispute, the attendant claimed, Trask struck her with his car and, after tempers grew heated, used a racial slur. When student protesters occupied the Allen Building for a week in 2016, after The Chronicle had reported the allegations, their workplace-related demands included Trask’s termination. Trask denied using the slur and said he did not intentionally hit the attendant. He did write to her, saying he should have been more patient and apologizing for the incident.

Today Trask doesn’t want to dwell on that episode. But he calls himself a left-of-center Democrat with a longstanding commitment to progressive values. He recalls his mother interrupting a study session and handing him, when he was a high-school student, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail,” a work he has returned to several times over the years. In college he protested against the Vietnam War. While in business school, he was stirred again into protest by the National Guard shootings at Kent State. He led his classmates in a walkout that extended through the last few weeks of the spring semester.

Such personal details resonate for Myrna Adams, who came to Duke just as Trask was starting, in the summer of 1995, as Duke’s first vice president for institutional equity. She calls Trask an affirmative-action leader at heart, and says she looked to him to support her work in diversifying the administration. Trask ran searches that brought persons of color to prominent positions, Adams says, and he hired the first Black architect to design for Duke (the late Durham-based Philip Freelon, who inaugurated Duke Brick) since Julian Abele, who shaped the fledgling university. And she says Trask went to bat for employees at the lowest salary levels, notably pushing to raise the minimum wage on campus.

More recently, Trask has helped lead the push for Duke to become carbon-neutral. (The original Campus Sustainability Committee, from 2007, was co-chaired by Trask and the dean of the Nicholas School.) The target year, 2024, is the university’s centennial year. In Trask’s view, that short time frame is a big challenge: It involves not just institutional gestures, but also individual decisions around driving to and from campus.

A decade ago, Duke ended the use of coal in its steam plant; at the time, coal was still the largest energy source in the state. Just this past summer, Duke announced that it would purchase 101 megawatts of solar capacity from three new solar facilities planned for North Carolina—a step long sought by the university and that finally became possible, according to Trask, with a change in North Carolina’s regulatory environment.

The energy innovation, the campus planning, the downtown footprint, the IT overhaul—it’s a long record of working to fuel the university’s ambitions. “I had this conversation with Nan Keohane after I’d been here a couple of years,” Trask recalls. “Duke was unsure of itself. It was insecure. It was this Southern place that was trying to be something else. There were these T-shirts that said, ‘Duke: the Harvard of the South.’ And I remember saying, ‘First, we’re not. Second, we don’t want to be.’

“My view has been, at least in the past decade or so, Duke is good enough and strong enough that it needs to figure out what it wants to be. And then, just get there.”

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor