Proof of prognostication: Detail from 1870 Koskoo Almanac!

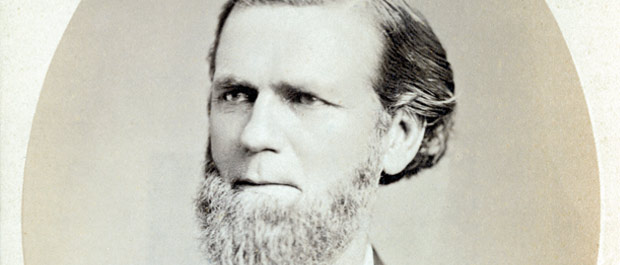

Although he never attended college himself, Braxton Craven—the longest-serving president in Duke’s institutional history—was a man of broad intellectual talents. A voracious reader, he enjoyed an excellent memory and an aptitude for a wide variety of subjects. As he led the fledgling Trinity College from 1842 to 1882, he was called on to teach an array of classes, including psychology, aesthetics, zoology, chemistry, ancient languages, and biblical literature. One of just six professors at the Randolph County school, he was officially listed in Trinity’s annual catalogue as a professor of metaphysics, rhetoric, and logic. He also served as the school’s physician, provided legal help to townspeople, and was noted for his expertise on everything from horses to economic development.

Perhaps the most extraordinary display of Craven’s abilities came in 1869, when the North Carolina minister outsmarted some of the best scientific minds in the country. The occasion was a solar eclipse that was to occur over the eastern U.S. on August 7 of that year. The venerable Smithsonian Institution published a list of times when it predicted the eclipse would be visible over various cities, including Raleigh. But Craven did not agree.

Astronomy was another of Craven’s areas of self-taught expertise. His teaching notes on the subject, which are part of his papers held in the University Archives, include diagrams and mathematical formulas for predicting a solar eclipse. Craven’s own calculations for when the eclipse would be seen over Raleigh differed by a few minutes from that of the Smithsonian experts.

The day of the eclipse was the moment of truth. Sure enough, the skies over Raleigh darkened at the time Craven had predicted. It is said that the Smithsonian was so impressed with Craven’s prediction that they offered him a position at the institution. Little correspondence survives from the time period, and Craven’s diary does not mention the offer—in fact, he did not even include an entry for August 7, 1869. With the school year approaching and many preparations to occupy him, one can imagine he had little time to celebrate his triumph.

The day of the eclipse was the moment of truth.

In the years following the eclipse, Craven continued to dabble in astronomy. Among the Rubenstein Library’s collections is a small, bright-yellow pamphlet from 1870 titled The Koskoo Almanac!, which listed Craven’s detailed predictions for the rise and fall of the sun and moon, surrounded by advertisements for Koskoo, a supposed miracle cure derived from Mexican ivy. But if he was indeed afforded a chance to pursue his astronomical interests with the Smithsonian, he gave no indications of a desire to leave Randolph County. He remained Trinity’s president—and resident expert on just about everything—until his death in 1882.

At the time Craven made his calculations, there was no way of predicting that Trinity College would grow into Duke University, one of the largest research universities in the country. But the origins of Duke’s intellectual curiosity can be found in the young school—and its polymath president. On that day in August 1869, the sun may have gone out on Raleigh, but it shone brightly on Braxton Craven, and it was just beginning to dawn on his ambitions for Trinity College.

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor