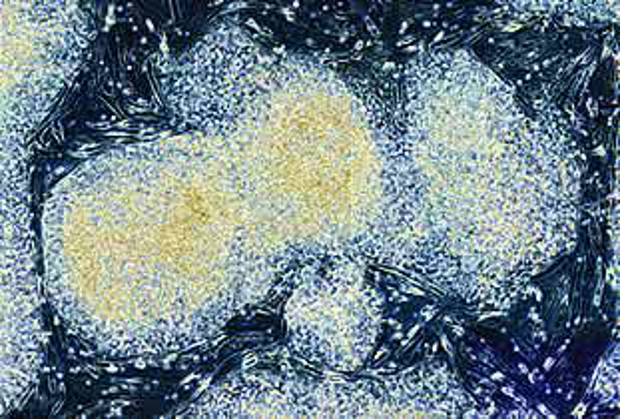

In ancient Bedouin parable suggests that if you let a camel stick his nose in your tent, before long, the whole camel will be in the tent. The phrase "the camel's nose" is another name for the usually fallacious reasoning known as "the slippery slope," in which one event is deemed to lead inevitably to another. With President George W. Bush's decision in August to allow the limited use of embryonic stem cells in federally funded research, the phrase "slippery slope" was in common use in academe. Scholars and scientists weighed in on the president's decision from a variety of angles--medical, ethical, religious, political, legal, and commercial. At the heart of the debate is a complex maze of questions. Do embryos created for in vitro fertilization have the same moral and legal status as persons before they are implanted in the womb, or are they the property of the parents? Do the potential benefits of curing debilitating disease outweigh the cost of destroying these human embryos to obtain their stem cells? What is the appropriate federal role in setting the boundaries of research on human subjects? Do embryonic stem cells really hold the immediate promise for the cure of chronic disease that has been reported in the press? Embryonic stem cells were isolated and grown in culture for the first time in 1998 by James Thompson, a developmental biologist at the University of Wisconsin. Thompson derived the cells from four- to five-day-old embryos, known as blastocysts. Stem cells--which are also present in adult tissues--have the capacity to grow into almost any specialized cell in the human body, such as heart, brain, liver, or pancreas. Thus, the potential use of stem cells to repair or replace diseased or damaged organs and tissues has become a subject of intense interest in the medical community and to patients suffering from diseases ranging from Parkinson's to diabetes to Alzheimer's. Because stem cells found in the early-stage human embryo are believed by many researchers to have a greater ability to transform themselves into many more types of specialized cells than stem cells derived from adult tissues, the National Institutes of Health requested an opinion from the Clinton administration's Department of Health and Human Services soon after the Wisconsin breakthrough. NIH wanted to know whether federal funds could be used to support research on human stem cells derived from embryos or fetal tissue. (The Wisconsin research and similar research at Johns Hopkins University had been privately funded by the Geron Corporation of California: Thompson, the biologist, extracted the stem cells from embryos left over from an in vitro fertilization, or IVF, procedure, embryos that had been donated by couples who underwent IVF.) The opinion rendered by Health and Human Services general counsel Harriet Rabb argued that the existing statutory ban on human-embryo research defines an embryo as an organism. Because human stem cells, once removed from the embryo, cannot develop into an organism, even if transplanted into a uterus, Rabb held that NIH could support research on embryonic stem cells but could not, under current law, fund research that actually harvests stem cells from embryos and thus destroys the embryos. The implicit presumption, then, is that federally funded researchers would have to obtain stem cells from private sources that have no restrictions on the destruction of embryos--the first of many slippery slopes. As might be expected, this ruling by the Clinton administration did not sit well with some members of Congress. In the presidential campaign, George W. Bush took a stand against government financing of embryonic stem-cell research, yet he was in office for eight months before issuing his surprise ruling to limit federally funded research to sixty-some existing stem cell lines already derived from human embryos and that are purportedly self-sustaining.

Researchers who had feared an outright ban from Bush were relieved. Others argued that the president's restrictions were too severe, and they questioned the viability of the sixty lines of cells that Bush claimed were already available to researchers. Still others considered the Bush decision only a short-term response to a much larger issue--namely, the absence of any comprehensive federal law regulating the parameters of medical experimentation on children or adults, whether that research is publicly funded or not. The potential of stem-cell research to crack open new avenues for the cure of chronic, debilitating disease caused even some of the staunchest opponents of abortion--such as Utah Senator Orrin Hatch and Tennessee Senator Bill Frist, a physician--to push the president toward his compromise decision. And already advocates of the research from both the anti-abortion-rights and pro-choice sides of the abortion issue are hoping that Congress will open the field beyond the sixty stem-cell lines. Amy Laura Hall, assistant professor of theological ethics at Duke Divinity School, is deeply troubled by the Bush decision to approve even the limited use of embryonic stem cells. "We have crossed a significant moral boundary without a sense of transgression and moral responsibility," she says. "While these are cells, they are not mere cells."

Hall recently spoke to a group assembled by Duke's Center for the Study of Medical Ethics and Humanities. In the same way that communion wine to a Catholic is not mere wine, nor is the soil of Israel mere dirt to a Jew, Hall argued, so too must we be encouraged to see the human blastocyst from which stem cells are extracted as more than a clump of cells. Hall, who is not a strict opponent of abortion, suggests that we must nevertheless recognize the blastocyst as nascent life and therefore sacred. "Which worries your average 'pro-life' senator more?" Hall asks. "The thought of women ending embryonic life, or the thought of a male-dominated, multi-million-dollar pharmaceutical industry using human embryos for research? It should come as little surprise that some supposedly pro-life leaders are making an exception on the issue." Kathleen Joyce, a historian in the department of religion, sees the situation differently. "The stem-cell debate is not converting or changing anyone's idea of where life begins," she says, "but advocates of the Bush policy are saying that the evil [destruction of the embryos to extract the stem cells] has already been done, and we can make use of it. Stem-cell research can be life-giving." The technological capacity to keep human embryos in storage indefinitely has preceded the full consideration of the legal ramifications of the warehousing of frozen clusters of human cells or whose property they might be. Doriane Lambelet Coleman, who teaches a course on genetics, genomics, and the law at Duke Law School, points out that "each clinic has its own protocols, individual state laws differ, and some clinics don't discard unused embryos even if the parents ask them to." She also points to a recent divorce case in Tennessee where the "custody" of these frozen embryos has even been contested.

If and when stem-cell research breakthroughs begin to have a significant impact on the amelioration of disease, the ownership and availability of frozen embryos may become an even greater concern. Hall worries that private interests will seek to buy these leftover frozen embryos for the harvest and sale of stem cells or seek to "manufacture" embryos for the explicit purpose of extracting the stem cells. At that point, she might argue, the proverbial camel will be in the tent. "It's important to note that we are talking about the alleviation of human suffering as the rationale for using embryonic stem cells," says Hall. "Yet there are all sorts of suffering that we have not been willing to prevent." She cites the continuing presence of lead paint in public housing as one example--poisoned children are still coming into hospitals because the public lacks the will to enforce environmental standards that are already on the books. "Those of us in the learned class who vote, listen to NPR, and live in gated communities have largely separated ourselves from many kinds of human suffering," she adds. "But no matter how much you protect yourself, you cannot prevent a child from getting diabetes or a husband from getting Alzheimer's." Hall, who would rather see researchers exhaust all avenues of experimentation using adult stem cells first, suggests that the public has been too quickly seduced by this new technological wizardry. It was precisely the promise of dramatic cures that was the steady focus of the medical establishment's media campaign on behalf of embryonic stem-cell research as the president began his deliberations. Though Bush had stated his pre-election opposition to stem-cell research, it was the intercession of Secretary of Health and Human Services Tommy Thompson--a longtime supporterof the right-to-life movement and governor of Wisconsin, where the first stem-cell breakthrough occurred--that reportedly caused Bush to delay his decision and consider a compromise. "The delay gave us an opportunity to educate the public," says Tony Mazzaschi, assistant vice president for biomedical research and health sciences and director of the Council of Academic Societies at the Association for American Medical Colleges. "We started a major effort in newspapers all over the country and did talk shows. We were directly responsible for more than 200 op-ed columns that were published, and we have gotten more than 200 positive editorials in the nation's newspapers. Our ability to get people talking about the issue has been phenomenal." Mazzaschi was one of the key speakers at a stem-cell research conference held at the Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy in October. Despite Mazzaschi's evident pride in the media campaign, Elizabeth Kiss, director of Duke's Kenan Institute for Ethics, says that creating hope for rapid cures potentially constitutes "an exploitation of the loved ones of those who are suffering from these diseases." Jeremy Sugarman '82, M.D. '86, director of Duke's Center for the Study of Medical Ethics and Humanities, also cautions against such easy optimism. "The assumption that the science is necessarily going to work is treacherous moral ground," he says. "What we've learned over the history of science and medicine is that our best ideas, once tested, don't necessarily pan out." The new dean of the medical school and vice chancellor for academic affairs at the Medical Center, R. Sanders "Sandy" Williams M.D. '74, agrees. "Media coverage leads to one major misperception, and that is that these therapies are simple," he says. "You don't just shoot stem cells into people and that takes care of it. We are going to have to deliver stem cells in clever ways that make them able to do their work. Real medical progress is going to be hard. Expectations are high. The public is going to be disappointed if they think this research is going to offer quick fixes." Williams, a cardiologist, is himself engaged in research targeting the possible use of stem cells in repairing diseased heart tissue. In addition to the concern about overselling the potential of stem-cell research, the protocols in the application of research findings in the treatment of patients present another set of challenges. Much of Sugarman's work in medical ethics has revolved around when it is appropriate to leap "from bench to bedside" with experimental interventions. "When will we know enough to make that leap?" Sugarman asks. "Will this stem cell turn into the kind of cell we want it to in the human body and continue to be that kind of cell? Or will it turn off or turn into cancer? Not only is having enough scientific knowledge critical, but also the informed-consent process we use with patients who submit to participating in research treatment is crucial here." Since 1994, Sugarman has worked closely with Joanne Kurtzberg, director of Duke's Pediatric Stem-Cell Transplant Program, to develop ethically based protocols for informed patient consent, confidentiality, and the safe collection, typing, storage, and use of umbilical cord blood to be used in the treatment of certain rare forms of leukemia and genetic irregularities in children. Kurtzberg's breakthrough work in administering transfusions of stem-cell-rich cord blood to infants as an alternative to bone-marrow transplants is a radically new and amazingly successful form of treatment to which Bush alluded in his stem-cell pronouncement.

Questions about ownership of the blood, the obligation to notify parents if medical tests conducted on donated cord blood detect the presence of infectious disease, and the need for a fair and equitable means of public access to the placental blood collected for treatment are also part of the considerations. Kurtzberg and Sugarman held a series of focus groups with pregnant women around North Carolina to determine what concerns their potential subjects might have about being asked to donate cord blood to the bank. They discovered that cultural differences also had to be considered in protocol development. Some cultures believe they must bury the placenta. Others use it in religious ceremonies. "To look at cord blood as a waste product is just one point of view," says Sugarman. Kurtzberg and Sugarman also discovered that some community hospitals were reluctant to allow cord blood from their patients to be banked. The hospitals in question had actually created a revenue stream for their operations by regularly selling cord blood--without the patients' knowledge--to cosmetic manufacturers who use "extract of placenta" as an ingredient in makeup. Just as new mothers had no idea that this by-product of birth containing stem cells was being sold without their consent, a number of ethicists worry about the potential "commodification of human life" that's possible through the banking of embryos at IVF clinics. Here yet another potential slippery slope emerges. "We have all these possible children in vats for our own reproductive convenience because it is inefficient to create only just what we need for in vitro fertilization," Hall says. Elizabeth Kiss of the Kenan Institute for Ethics does not share Hall's view that the destruction of existing embryos to harvest stem cells is a moral wrong that outweighs the potential benefits of stem-cell research. But she does draw the line at the notion of creating embryos for the specific purpose of harvesting stem cells. "I worry about commerce in human embryos," she says. "We should think seriously about the reproductive technologies that have led us to create all these IVF bodies in the first place." "We are already engaged in the commodification of women and children," says the law school's Doriane Lambelet Coleman. "People don't want to talk about that, but women's eggs are already for sale, and at a much higher price than sperm because the extraction of the ovum is much more difficult." She notes that websites like www.eggs.com graphically demonstrate how private interests are already engaged in this business. Does the federal government have a responsibility then to go beyond the invisible hand of the marketplace to prevent human life from becoming a commodity? Coleman suggests that the notion that we could ever discern how many cells make something human is finally "a political decision based, hopefully, on science. But that line can be drawn differently in different countries." She argues that the Bush decision to limit publicly funded embryonic stem-cell research only to those cells extracted before his announcement, on August 9, may, in fact, have the unintended consequence of driving much of the embryonic stem-cell research and subsequent commerce offshore. Coleman's law school colleague, Lauren Dame, is the associate director of Duke's Center for Ethics and Genome Policy. She is also concerned about the quality and protocols of private stem-cell research. "Ironically, if you are concerned about the ethics of the research, it seems to me that you would be in favor of federal funding, so that the research is conducted with governmental oversight," she says. "If private companies are the ones doing stem-cell research on frozen embryos and the research is successful, then companies may go quickly to making embryos explicitly for the purpose of research."

Medical School Dean Williams agrees that creating embryo "farms" to harvest stem cells would be inappropriate, and he also worries that the Bush decision might inadvertently make this possibility more likely. Williams says the sixty cell lines are "an artificial limit, the basis for which is unclear." Having an artificial limit may turn out to be a serious impediment to progress, he argues. Nor does he believe it is feasible or in the best interest of achieving positive results to confine the government-funded research only to adult stem cells. "We know that cell lines maintained in culture change over time and may be less useful," Williams explains. "Opening the research field to the use of any embryos already slated for destruction would be a more reasonable choice. By limiting research to cell lines created by companies, academic institutions are put at a disadvantage, which is exactly the opposite of what, I think, you want to do. Academic institutions [that receive federal funds] are about serving the public, performing open research, and publishing the results of that research for the benefit of everyone. Corporations have a first allegiance to their shareholders. If there is an ethical dilemma here, I think it is in creating a policy that disadvantages academic institutions." Dame is concerned that, at times, the debate has been oversimplified. "I have heard proponents of embryonic stem-cell research argue that anything less than unrestricted research is simply delaying the discovery of cures for terrible diseases," she says. "This assumes that the severity of the disease is the only consideration. We may decide that creating embryos to use for research is the lesser of two evils, with the terrible suffering caused by diseases being the greater evil. But we have to recognize that this is a difficult choice, and we would be taking a huge step over a moral line. Otherwise, we may find ourselves in a place where it is not too much of a jump to say that some lives are more valuable than others." On one point, most thinkers seem to agree. By approving the limited use of embryonic stem cells in government-supported research, Bush shifted the debate overnight from "whether" to "how many," and from there, the consequences are unclear. Joanne Kurtzberg, Duke's path-breaking researcher, thinks the brouhaha may be overblown. "Personally, I believe that embryonic stem cells will not ultimately be necessary," she says. "Eventually, we'll only need the DNA." But, she points out, Bush's preservation of a federal role in stem-cell research is extremely significant. Her own work with cord blood stem cells would never have happened without NIH support, she says--the diseases she is treating are too rare for the treatment to be profitable to private interests. "If marketing drives the research, it will bias the research," she says, and researchers will only be encouraged to seek discoveries that hold the promise of a significant return on investment. Though Kurtzberg's work is also now supported by the Red Cross and the American Cancer Society, she still maintains that "when you need a lot of money, the government is the best place to get it." For his part, Williams believes that we have entered "the heroic age of biomedical science," and that Duke is well positioned to be driving some of the advances. "These transforming events are disruptive and sometimes challenge our sense of right and wrong," he says, "but these decisions will not be left to science alone. We need to govern ourselves in a wise manner and inform the public about the potential for discovery." Continuing the conversations about the ethical implications of such technological breakthroughs is the most crucial element, says religion historian Joyce. Duke's interdisciplinary approach to the dialogue is part of a relatively new trend. "It is helpful to get a perspective on how recent these concerns are. Some critics have suggested that the U.S. is a society adrift downward, not being sensitive to moral and religious issues." Joyce argues to the contrary that the last twenty-five years have been unique in the increasing attention being paid to the intersection of medicine and ethics. "In the past, men of science made decisions based on scientific criteria," she says. "So much of what was done in medicine in the past was done out of sight. People were not aware of the sterilization of developmentally disabled people or the choice some doctors made not to treat severely ill infants." Medical information today, she suggests, is more widespread than ever. "Technology is so often seen as this sterile agent of modernity," she adds, "but the opposite is true." As an example, she cites the cell-phone calls and e-mail messages sent from the World Trade Center at the time of the September 11 attacks, which made the disaster all the more human and real to us. "What is difficult about our situation now," says Joyce, "is the pace of research. Developments in the past were much more incremental and spaced out over time. Bringing our religious beliefs to bear on these issues both humbles us and forces us to confront the limits of our power and finitude and to induce a constructive discomfort." And this discomfort, Joyce would argue, is ultimately healthy. Eubanks '76 is a frequent contributor to the magazine. |

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor