Something was rotten in the German village of Langenburg. Or was it someone?

The year was 1672. On Shrove Tuesday, Eva Kustner, the miller's daughter, had gathered up freshly baked sweets provided by her mother. She had then delivered some to a neighbor, Anna Fessler. Such exchanges marked the central event of the holiday, a gesture that reinforced family and neighborly ties. But these particular ties had terrible consequences. Hours after consuming one of the cakes, Fessler, a new mother in apparently robust health, was overcome with pain. Soon she was dead.

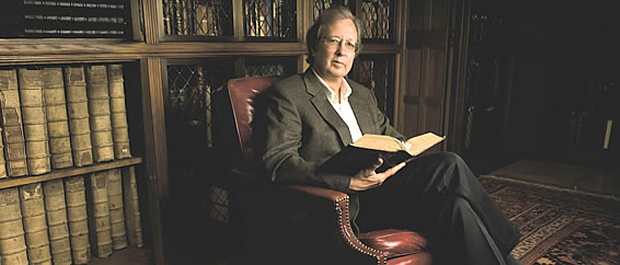

That was the beginning of an unhappy episode that played out in more distress and death. Centuries later, it would become the preoccupation of Duke history professor Thomas Robisheaux.

"I never wanted to write about witchcraft," says Robisheaux '74. His graduate-school mentor at the University of Virginia, Erik Midelfort, had helped establish witchcraft and witch-hunting as a mainstream topic for early-modern historians back in the 1970s. Robisheaux wasn't inclined to work in the shadow of his mentor. But he had come to notice how little historians understood about women, especially peasant women, in the early-modern period: "And one of the places you look for rich material about women for this period is trial records, especially witch trials," he says. The subject of this witch trial, Anna Schmieg, Eva Kustner's mother, promised a rich line of research.

During fifteen years of research, Robisheaux sifted through government and church records, eyewitness recollections, and an autopsy report to flesh out the lives of Anna Schmieg and the people around her. He spent endless hours in the regional archives, housed in a castle, to piece together individual lives; visited libraries to read through contemporary legal and medical tracts; and took a month to hike the area, with the aim of sharpening his sense of the landscape. He calls the book that resulted, The Last Witch of Langenburg: Murder in a German Village, a "micro-history." The small setting of Langenburg serves as a model of broad cultural trends—and an avenue into understanding a traumatized society.

Illustration by physician Gottfried Welsch, who pioneered autopsy techniques like those used on the Langenburg poison victim.

Illustration courtesy W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

"These were societies that were fragmented and localized," he says. "Most people in Europe had no general sense of events on a large scale across a kingdom or even over a province. But they took into their lives the bigger trends, the trends that historians might talk about for the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The other thing about micro-history is that, as a technique, it works best for events that come before a court or an inquisition. You can see in the protocols, in the interrogations, the semblance of a popular voice."

If Robisheaux's work has a detective-story quality, the plot was hatched—or cooked—in the kitchen of the miller's wife. The mill still exists, though in a rundown state. Robisheaux and his wife visited it a couple of years into his research; as they were looking it over, a voice called out, "You know, a witch used to live there!" That voice turned out to belong to the woman who owned the mill and was renovating it as a dwelling. Robisheaux says he was stunned to see the persistence of the story after more than 300 years.

Seventeenth-century millers were seen as little better than rogues or thieves, existing on the margins of society, along rivers or streams at a village's edge. Hans Schmieg, who collected black cats, was suspected of using sorcery to repair and protect the millwheels in their daily operation. Maybe the millwheels were functioning smoothly. The agricultural economy, though, was in a freefall. When crops failed or soldiers destroyed the fields, local supplies dried up, and prices for grain and bread soared, feeding community resentment. But governments fixed prices for grain and—in a coupling of welfare-state mentality and Christian morality—required that millers take care of neighbors first. Profit-minded millers resisted such rules, often choosing to sell grain supplies out of the territory.

Hans Schmieg's transgressions involved more than rules-bending. In one incident, he assaulted the count who happened to be his patron and lord. But his wife, Anna Schmieg, was the more mysterious figure. A refugee from war and plague, she had lost her parents early and was sent off to relatives as a domestic servant. She was, as Robisheaux describes her, an eternal outsider and a tenacious survivor. "Anna spent her formative years among villagers thrown on their own wits and meager resources to survive."

In Langenburg, she was known for drinking to excess, insulting her peers at the local tavern, and threatening to kill a neighbor's cattle when they grazed on her property. She was thought to engage in whispered conversations with the devil. She was also very protective of her husband—to the point of lashing out at the count's steward when he fined Hans for illegally selling a cow. The steward would label her "this well-known good-for-nothing woman" who was given to wine along with "quarrels, brawls, shocking curses, swearing, and blasphemous insults of all kinds."

An inherent aspect of village life was "a culture of slander and assault that was highly developed," says Robisheaux. "If you didn't stand up when somebody insulted you, you invited more attacks. Or if you didn't answer a charge, gossip would start that, hey, you might actually be guilty. Women were good at this. They had to be.

"What makes Anna different from other women is that she always knew how to best someone. So in a verbal exchange, she would calibrate the insults one notch sharper. Or, in some cases, she would turn to physical violence, too, which for a woman was very unusual."

A mid-seventeenth-century phenomenon that was hardly unusual was the witchcraft trial. Robisheaux estimates that of the 100,000 trials in Europe, more than half were in the German lowlands, the result, he says, of fragmented legal cultures. "The big centralized monarchies like France and Spain were very reluctant to prosecute witch trials. But Germany had no centralized monarchy. It was really a bunch of small territorial states. These individual courts could pretty much do what they wished in their own jurisdictions. The authorities lived close to the events, and they could be drawn into the dynamics of witch fears much more readily than, say, a review judge sitting in Paris."

Especially in small, tight-knit communities, it was difficult to accept the notion that random forces could explain misfortune. And this was a time and place of relentless misfortune. The German countryside was often plagued by crop failures. It was also plagued by painful memories of the Thirty Years' War, which had raged from 1618 to 1648—an event that Robisheaux portrays in apocalyptic terms. When an invading Catholic military force quartered in the German countryside, "they would strip the countryside bare," he says. "And the hell with what the peasants needed to get by in the winter. They starved to death. Whole villages would flee into the woods and live off of whatever they could forage there, or become refugees on the roads."

Sealed fate: Legal opinion of the Faculty of Law at University of Strasbourg, October 8, 1672, to Langenburg, stating that Anna Schmieg could be interrogated a second time, using torture.

Courtesy W.W. Norton & Company Inc.

Humans are "meaning-making machines," as Robisheaux puts it. "We are always looking to make sense out of events that present themselves as chaos and confusion, especially if those events impinge on our lives in a very direct way." In the early-modern period, supernatural forces, including those unleashed by witchcraft, provided ready-made explanations for tragedy.

In the book, Robisheaux describes the trial and related events as following the script of a Baroque drama. That's a particularly apt analogy. "The whole court culture was saturated with reading German Baroque dramas, which were tragic and horrifying stories," he says. And the story of intersecting lives and a mysterious death in Langenburg fit the familiar pattern: Hidden in the most seemingly mundane events was something deeper and more cosmic.

At least in this case, the legal process itself was structured like a classic Aristotlean formulation: a dislocation, an investigation, an explanation, and finally a resolution. The formidably named Tobias Ulrich von Gülchen, the chief magistrate, did not leap to conclusions like the stereotypical crusading witch-hunter. He never considered suspending the so-called "ordinary law" and its rules; he never treated the case as an "exceptional crime." This fact alone, says Robisheaux, "distinguished von Gülchen from magistrates earlier in the seventeenth century, who, when facing possible cases of witchcraft, shortened the legal procedures and suspended normal rules of evidence. In these cases the law had been a crude instrument of persecution of suspected witches."

The ten-month trial to a great extent revolved around a mother-daughter dynamic: The mother, Anna Schmieg, the miller's wife, had baked the suspect cakes; but her daughter, Eva Kustner, had been the delivery agent. Von Gülchen aimed to break the family bond through the accepted tactic of confrontation, provoking Eva to assign guilt to Anna. Then, in the presence of her mother, the daughter was made to repeat the accusations.

"Just like they are today, mother-daughter relationships were very close but emotionally charged," Robisheaux says. "Sometimes the boundaries between mothers and daughters are not so clear. Daughters know mothers in ways mothers don't even know themselves, and vice versa. Witchcraft in this time was thought to be a black art that was taught in secret from mother to daughter. And by breaking open this relationship, the chief magistrate was trying to get at the truth of what had actually happened."

Robisheaux says that women's labor was essential for early-modern society to work. Witchcraft was women's work that went wrong, then, in areas like pregnancy, childbirth, the health of children, tending cattle, and the fertility of crops. "You might say that witchcraft blighted life where women were supposed to nourish it."

Von Gülchen's labors included arranging an autopsy of the presumed poison victim. For that service he turned to Altdorf University, one of a handful of Protestant universities at the time. Like jurists, physicians of the period were considered truth-seekers who prized firsthand observation. A chief innovator was Moritz Hofmann, professor of anatomy and surgery, who championed William Harvey's then-radical theory about the circulation of the blood. But his ideas about the human body still accommodated "animal spirits" and other supernatural influences. Hofmann confirmed a cause of death that was consistent with poisoning—and with witchcraft.

Such illustrations of "the two-faced nature of the period" are alluring for Robisheaux. "There are aspects of the society that are decidedly archaic and strange and bizarre and don't seem to go anywhere into the work of making modern Europe. And those are just mixed willy-nilly with developments that lead right into the present day. That makes the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries particularly fascinating and complex."

In the late stages of the trial, Anna Schmieg was subjected to torture on the orders of the chief magistrate, with the aim of achieving a confession; von Gülchen, ever-mindful of proprieties, reached out to esteemed legal thinkers to support the decision. The procedure was grisly: Her hands were tied behind her back, and she was hoisted up on a pulley; later, her thumbs were twisted in thumbscrews.

In the late stages of the trial, Anna Schmieg was subjected to torture on the orders of the chief magistrate, with the aim of achieving a confession; von Gülchen, ever-mindful of proprieties, reached out to esteemed legal thinkers to support the decision. The procedure was grisly: Her hands were tied behind her back, and she was hoisted up on a pulley; later, her thumbs were twisted in thumbscrews.

Robisheaux's account points to a sort of tortured logic behind a forced confession. "To proceed to torture and not elicit a confession was tantamount to an admission that the law had failed, that the evidence was deficient, that the truth remained elusive or unknown, or worse, that the judge and the court were committing an injustice." Torture was considered, then, not just an aspect of justice but, as the occasion demanded it, a prerequisite for justice.

Still, Robisheaux doesn't find von Gülchen, who spent much of the investigation bedridden with an unknown painful illness, an unsympathetic figure. "He was dealing with a known threat. If you didn't show determination in rooting out this evil, you had a real public panic on your hands. That's what he wanted to demonstrate to the public—that the state could, through its investigative techniques and the proper execution of the law, find these domestic threats and restore order."

With seeming inevitability, the investigation led to the execution of Anna Schmieg. Robisheaux writes that "immense spiritual, psychological, and emotional pressure" had led her to a form of confession and conversion. "Law blended with theology to compel her to trace her identity as a witch back to an entire life of sin and crime." Her story of wrongheaded desire and deed would be affirmed "voluntarily" in her own words. But the story didn't proceed precisely as scripted. When asked to elaborate on the details of her secret life as a witch, she balked. When invited to show complete repentance, she couldn't find the words. Finally, von Gülchen simply drew up a list of charges on a document that she ended up signing.

Villagers were obliged by law to attend the executions of witches; choirboys would be assembled to sing hymns in the procession to the pyre. Witchcraft was considered to be apostasy, Robisheaux says. "It was turning against God and the state, so it was a double crime. It was undermining public authority, but it was even worse than treason, because it was renouncing the sovereignty of God and Christ and renouncing your own baptism, which was unthinkable in a devout, orthodox Lutheran culture. That's why it had to be punished with a public spectacle. It was a sermon in action."

But was this particular sermon in action perhaps based on criminal behavior if not on witchcraft? Robisheaux acknowledges that he has a hard time believing that Anna Fessler, the consumer of the proffered cake, wasn't a victim of a foul deed. "It just doesn't make a whole lot of sense," he says, that the young mother "would die suddenly, dramatically from some violent illness." Comparing the description from Fessler's autopsy with standard accounts of medical symptoms, he concluded that her demise was perfectly consistent with acute arsenic poisoning. Millers were among the few who could buy arsenic to control vermin.

What's less certain, he says, is the target of Anna Schmieg's wrath. Robisheaux speculates that she was pursuing not a neighbor but rather her son-in-law, Philip Kustner, "the rogue who had gotten the daughter pregnant and brought scandal into the family." For their improper relationship, the not-yet-newlyweds had endured two weeks in prison. The daughter's forced marriage to Kustner, a supposed village idiot with no claims to property, had disturbing economic consequences for Hans and Anna Schmieg: It ended prospects for an alliance with a wealthier family that might see the couple through retirement. (The likely scenario, in Robisheaux's view, is that Eva Kustner was an unwitting accessory: She delivered that fatal slice of cake to a friend, someone for whom it was never intended.)

Von Gülchen's successor as chief magistrate was much more secular in his orientation. In his court a decade later, this would have been a trial for murder and not witchcraft, Robisheaux says. And European witch trials ended completely by the eighteenth century. The theological idea of witchcraft as a pact with the devil fell out of favor, just as an increasingly materialistic science denied supernatural explanations of poisoning.

But in parts of rural Europe, the fear of witches continued well into the twentieth century. In 1944, Britain invoked its witchcraft laws to prosecute "Hellish Nell," a Scottish seer. The fear was that she might use her powers as a spirit medium to reveal the Allies' secret plans for the Normandy invasion. This was the last known prosecution of someone under the British witchcraft laws before they were abolished in the early 1950s.

"The witch is just a variation on the bigger term of 'the other,' " Robisheaux says. "Societies almost always locate their fears, real or imagined, in those who seem to embody the opposite of all that is valued.

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor