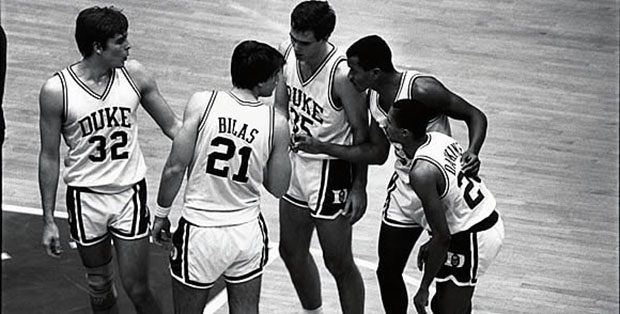

On December 5, 1981, the Duke men's basketball team lost at home to Appalachian State University, 75-70. The next morning the telephone rang at the Rolling Hills, California, home of Jay Bilas, a high-school senior, an excellent student, and one of the nation's top prep basketball players. His mother answered the phone. The voice on the other end asked whether she had ever heard of Appalachian State. She replied that she had not. "Well," the voice said, "they're the school that beat Duke last night." Duke was one of the universities Bilas was considering attending. The voice on the phone belonged to an assistant coach at another school recruiting Bilas. The message was clear: Bilas would be wasting his time at Duke. Bilas would have the last laugh. He would go to Duke, and he would excel there, both on and off the court. By the time he was a college senior, he and an exceptional group of classmates would return the Blue Devils to the top of the college-basketball universe. More important, they would set the stage for Duke to become a perennial national powerhouse and for Mike Krzyzewski to emerge as one of the best-known and most accomplished coaches in the history of men's college basketball. In those days, Duke wasn't the kind of university that ordinarily lost to midlevel Southern Conference teams. In fact, under head coach Bill Foster, they had played for the NCAA title in 1978 and made it to the Final Four in 1980. But in 1981-82, Duke was struggling. The new coach, Krzyzewski, was an unknown and unproven entity. Krzyzewski had come to Duke in the spring of 1980 to replace Foster, who resigned to go to the University of South Carolina. Duke's athletics director, Tom Butters, stunned the basketball world when he hired the thirty-three-year-old Krzyzewski, who had just completed his fifth season as head coach at the U.S. Military Academy. He was considered an up-and-comer in the coaching profession but he had little national recognition and no experience as a head coach in a high-profile league like the Atlantic Coast Conference. The day after he was hired, a headline in The Chronicle read, "Krzyzewski: This is Not a Typo." The Duke players were as much in the dark as everyone else. "I had never heard of him, never heard him mentioned," recalls Vince Taylor, then a rising junior. "I was stunned." Krzyzewski inherited three future NBA players--Taylor, Gene Banks, and Kenny Dennard--who helped his first Duke team reach the National Invitation Tournament. But all three were upperclassmen, and he knew he had to replenish the cupboard from the high-school Class of 1981 if Duke was to stay competitive. Over the course of that recruiting season, a half-dozen of the nation's top prep players narrowed their choices to Duke and another university. None chose Duke. The depleted 1981-82 Blue Devils won only ten of twenty-seven games. Krzyzewski couldn't afford another bad recruiting class. With his back to the wall, he hit the recruiting equivalent of a slam dunk in 1982. The first two players he signed were forwards Bill Jackman and Weldon Williams, from Nebraska and the Chicago suburbs, respectively. Next was Bilas, the six-foot-eight forward, who narrowed his choices to Duke, the University of Arizona, and Syracuse University. "I honestly didn't know where Duke was," recalls Bilas, now a basketball analyst for ESPN. He came to Duke because of Krzyzewski. "He explained how he would build the program, how we would win. I trusted him. It's as simple as that. He was honest, straightforward, and never wavered. I wanted to play for him." Bilas committed to Duke in January. A few months later, Krzyzewski signed another highly-touted six-foot-eight forward, Mark Alarie, from Arizona. The key recruit was much closer to home. Johnny Dawkins was a thin, mercurial guard from Washington, D.C. Blessed with speed, leaping ability, and shooting skills, Dawkins was coveted by every top college program in the country. "I grew up an ACC fan and always saw myself playing in the league," says Dawkins, now an associate head coach under Krzyzewski. "I remembered Duke's great teams from the late 1970s, so I knew the school could compete. The academic reputation was terrific, but, ultimately, it was the people who sold me, especially Coach K. He did such a great job of recruiting me as an individual, painting a vision for my future. He was fiery, competitive, and knew where he wanted to go and how to take us there." Krzyzewski recalls that "Johnny was our first legitimate big-time recruit. He could take the tough shots, win the tough games that we had not been winning." Krzyzewski completed his class with the largely unheralded David Henderson, a tough-as-nails perimeter player who had just led Warren County High School to the North Carolina 3-A state championship. The six freshmen joined eight upperclassmen, three of whom were left over from the Foster days. The ACC was a rough neighborhood in 1982-83. Top players in those days did not routinely go early to the NBA. Ralph Sampson, a seven-foot-four senior from the University of Virginia, was making a run for his third consecutive national player-of-the-year award. Sophomore Michael Jordan and junior Sam Perkins anchored a powerful North Carolina team. Both Virginia and North Carolina would be ranked number one in the weekly national polls at different points during the season. A trio of seniors--Thurl Bailey, Sidney Lowe, and Dereck Whittenburg--would lead North Carolina State to the 1983 NCAA title. The prudent course would have been for Krzyzewski to start his most experienced players, gradually working in the freshmen. Yet he gambled on youth over experience. The freshmen moved into the rotation from the beginning of practice, taking playing time from more experienced players, not all of whom took it well. Krzyzewski's most controversial decision was his refusal to play zone defense; throughout his career, Krzyzewski has been a strong proponent of an aggressive man-to-man defense. Alarie characterizes it as being "thrown into the deep end of the pool." It was a necessary risk, Krzyzewski says. "We finally had a group of kids who were going to be good, but it was going to take some time. We had a plan and were going to stick with it. Defense was going to be our foundation. It would have been foolish to wait." The learning curve was steep, and the freshmen struggled. The nadir may have been Duke's 109-66 loss to Virginia in the ACC Tournament, still the largest margin of defeat in Duke history. After the Virginia game, the Duke staff went out to get a bite to eat. Johnny Moore, a member of the sports-information staff, raised a glass and proposed a toast. "Here's to forgetting tonight." A defiant Krzyzewski interrupted, "No! Here's to never forgetting tonight." (Duke won its next sixteen games against Virginia.)

The Blue Devils finished the 1982-83 season with seventeen losses. The freshmen had obvious potential, but not everyone could see it and not everyone was willing to wait. Butters was inundated with demands to fire Krzyzewski. "We found out who our friends were," Bilas says. "Even the students didn't come around until our sophomore year. One Iron Duke actually showed me a petition demanding that Krzyzewski be fired. I don't know if he expected me to sign it or not." The six gained valuable experience over the summer when the team toured France. By NCAA rules, Duke couldn't take its departing seniors or its incoming freshmen. The rising sophomores circled the wagons and had what Dawkins calls "an amazing bonding experience. We really came together." The group did the requisite tourist stuff, but the trip was about basketball. "We were all winners in high school, and we all expected to be winners in college," Henderson says. "Our first year was tough. The trip to France gave us a chance to get the bad taste out of our mouths, to play some winning basketball. We got in the foxhole together." When they got out of the foxhole, they were better basketball players individually, and, perhaps more important, they were stronger as a team. But there was some attrition. Jackman lost playing time at the end of his freshman year and transferred back home to the University of Nebraska. Williams overextended himself academically with a difficult biomedical-engineering program and played sparingly while catching up. The other four sophomores continued to refine their games. Alarie was smooth and efficient, a silent assassin. Henderson was his polar opposite, a ferocious competitor whose take-no-prisoners approach was ideal for winning games. Dawkins benefited from the addition of freshman Tommy Amaker, a defensive stopper and skilled playmaker, who shouldered the ball-handling burden. "Tommy gave me the freedom to make plays," Dawkins says. "I wanted to attack, to beat the other team down the court, and he gave me that opportunity." Dawkins became the best-conditioned player in Duke history, running exhausted opponents into the court. Bilas faced the biggest adjustment. He was a natural forward, but Krzyzewski put him at center full time. He anchored himself to the post, frequently guarding players a half-foot taller. "I kept expecting a center to come along who was good enough to move me to forward," Bilas recalls. "But it never happened." Alarie was grateful. "Jay made so many sacrifices for the team, living in the weight room, setting screens for me to get open, guarding the giants so I didn't have to." Duke put the turbulent 1983 season in the rearview mirror. They finished third in the ACC in 1984, knocked off Jordan and top-ranked North Carolina in the ACC Tournament, and earned a spot in the NCAA Tournament. After the season, the school renewed Krzyzewski's contract, and there was no more talk about finding another coach. The following year, 1984-85, Duke won its first twelve games and jumped to number two in the polls. They won in Chapel Hill for the first time since 1966 and went on to finish just one win out of first place in the ACC. But injuries to Alarie and Henderson torpedoed the Blue Devils' postseason efforts, and the season ended with a bitter 74-73 loss to Boston College in the second round of the NCAA Tournament. Dawkins and his fellow seniors approached the 1985-86 season, their last, with a mixture of anticipation and determination. Bilas says, "We looked at the schedule and asked, 'What games can we not win?' We didn't see any, so that was our goal: Win every game." As it turned out, Bilas had to have knee surgery in the off season and was held out of the season's first six games as a precaution. He was replaced in the starting lineup by highly-regarded six-foot-ten freshman Danny Ferry. Williams' father pushed him to transfer rather than continue to ride the bench in games, but his son refused. "I was not a quitter," Williams says. "Besides, I was an optimist. I figured I would earn some playing time." That never happened; instead, Williams made his most important contributions in practice. Dawkins remembers that Williams "cut no slack, made the starters work every day, made us better." Dawkins, Alarie, and Henderson played the best ball of their careers. They had to. The ACC was loaded in 1986. Georgia Tech started the season ranked number one in the AP poll, just ahead of North Carolina. Duke was ranked sixth. One of these three teams would be ranked number one every week of the season. Then there was the nonconference schedule. Duke started the season by playing eight games in sixteen days in five states. The highlight of this stretch was defeating St. John's University and the University of Kansas at Madison Square Garden to win the preseason NIT. Duke won its first sixteen games, jumping to third in the polls. The Blue Devils didn't taste defeat until mid-January, when they lost back-to-back road games to North Carolina (in the first game played at the Dean Smith Center) and Georgia Tech. Alarie says he remembers "Coach K tearing into us after the Tech loss." But instead of panicking, they redoubled their efforts. "This was the point where we decided if we were going to be a great team or not," Alarie says. "We decided to be great. We got back to work and vowed not to lose again." Win followed win. Everyone knew his role. Bilas and Ferry supplied rebounding and interior defense. Amaker handled the ball and disrupted opponents' offense. Alarie and Henderson were versatile scorers. Dawkins was the nation's best guard, perhaps even the best player. Four years of playing together had given the team a distinct personality: poised, cohesive, and calm under pressure. They were at their best in close games, and would go on to win nineteen games by ten or fewer points. "We had almost total confidence in our ability to win a close game," Henderson says. "Somebody was going to come through and make the big plays. We just played so well together." One particularly tough weekend in February exemplified those qualities. Duke edged North Carolina State 72-70 in Raleigh on Saturday night as Dawkins made two free throws with one second left. The next day, back in Durham the Devils defeated a powerful Notre Dame squad 71-70 as Dawkins blocked a last-second shot. By the end of February, Duke was on a roll and had climbed to number one in the polls. "Coach surprised us when he made a big deal after our win [on February 26] against Clemson," Bilas recalls. "It was our twenty-eighth win of the season and broke the school record. He told us to savor it." Duke finished its regular season at home against UNC. A lot was at stake. It was the final home game for the five seniors. A win would give Duke the regular-season title. And it was UNC. The usually stolid Alarie was so pumped that he had trouble sleeping the night before the game. The Blue Devils played through their jitters and pulled away down the stretch for an 82-74 win. "We didn't play that well against UNC," Alarie says. "But our defense won it for us. Good defense is a constant. We knew we could shoot poorly and win, rebound poorly, and win, as long as the defense was there." The ACC Tournament was next. Wake Forest fell; then Virginia, bringing on a title match against Georgia Tech, whose star seniors, Mark Price and John Salley, had battled the Duke seniors for four years. Duke led by as many as nine points before falling behind late in the game. With only seconds left, Alarie made a short jumper over the outstretched arms of Salley to give Duke the lead. Dawkins rebounded a miss on Georgia Tech's next possession and finished off the Yellow Jackets with two free throws. The Blue Devils escaped with a 68-67 win. This marked the first season since 1966 that Duke had finished first in the ACC's regular season and won the conference tournament. Duke entered the NCAA Tournament as the top seed and was rewarded for its success with opening rounds in nearby Greensboro. But in the first game, against lightly regarded Mississippi Valley State, Duke almost laid an egg. Playing at noon on Thursday in a half-empty Greensboro Coliseum, Duke trailed for thirty minutes. The players were tired, overconfident, maybe even a little smug. Mississippi Valley State had a small but exceptionally quick team that, Bilas says, "pulled us away from the basket, took us out of our comfort zone, made us do things we weren't accustomed to doing."

Dawkins refused to let Duke lose, at one point banking in a basket while being pounded to the floor and converting the free throw for the three-point play. He scored twenty-eight points, and Duke won, 85-78. After the game, Dawkins quipped that some day he would come asking Mike Krzyzewski for a job. If the coach gave him a hard time, he said, he would mention this game. Henderson notes that after this shaky opener, "Coach had our undivided attention." The refocused Devils exploded. "We decided to attack the other team instead of having the other team attack us," Krzyzewski said at the time. Old Dominion fell, 89-61, followed by DePaul, 74-67. Playing in New Jersey, Duke met Navy for the Eastern Regional title. Navy had All-America center and future NBA star David Robinson, but its backcourt was badly overmatched. Duke broke open the close contest with an 18-2 surge to end the first half, a run Dawkins punctuated with a spinning, gravity-defying dunk over the earthbound Navy big men. In the second half, the All-America guard again led the way, ending the game with twenty-eight points, while Bilas battled Robinson to a standstill on the boards. Duke won, 71-50. The 1986 Final Four was held in Dallas. Top-ranked Duke opened against second-ranked Kansas, a big, physical team. The game was a tough, exhausting struggle in which each possession was precious. Duke led most of the way but never by very much. Kansas rallied for a 65-61 lead with just over four minutes left. Duke's defense went into high gear, holding Kansas to a single basket over the last four minutes and twenty-one seconds. Alarie tied the game at 65 with a dunk, drawing a fifth foul from Kansas star Danny Manning. Ferry scored on a rebound to give Duke a 69-67 lead. "It was a blood-on-the-floor kind of game," says Alarie. "We were exhausted, but somehow we had to suppress the fatigue and fight through it." Duke wasn't too tired to make two last defensive stops. Ferry drew a charge on Kansas' Ron Kellogg, and then Kellogg missed a jumper. Duke rebounded, and Amaker ended the scoring at 71-67 with two free throws. As usual, Dawkins was the leading scorer, with twenty-four points, but Alarie's defense on Manning was equally important. Alarie held Manning to four points, thirteen below his season average. The win was Duke's thirty-seventh of the season, setting an NCAA record that has been equaled but never surpassed. It put Duke into the title game against Louisville. Louisville jumped to a 6-2 lead. Duke soon caught up and led for the next thirty-three minutes. For much of the game, it looked as if Duke had the Cardinals on the ropes. But several fast-break opportunities were squandered, as passes were fumbled or easy shots missed. Louisville dominated rebounding, but Duke's defense forced twenty-four turnovers. Dawkins was unstoppable early, scoring thirteen of Duke's first twenty-five points. He had twenty-two points with fifteen minutes left when Louisville adjusted its defense to make it more difficult for Duke's star to get the ball. He made no field goals for the remainder of the game. This left good shots for Duke's other players, shots they had made all season. But fatigue was taking its toll. Duke was playing in its fortieth game of the season, and the Kansas game had left its share of bruises. "I was a shooter," Alarie says, "and shooters know: I kept taking shots that I knew were good, and they kept coming up short. It began to play on my mind." It wasn't just the shooting, Henderson says. "I didn't have any explosion. I was a half-step late for loose balls I usually chased down, rebounds I usually grabbed." Henderson, Alarie, and Amaker made only twelve of thirty-six field attempts for the game. Louisville caught up and took the lead at 64-63. The teams traded baskets until Louisville called timeout with forty-eight seconds left and a 68-67 lead. The Cardinals had only eleven seconds left on the shot clock. "We knew if we played good defense, we were going to have a chance to win it all on the last possession," says Dawkins. Duke played great defense. Louisville tried to get the ball inside but failed. With the shot clock about to expire, Louisville's Jeff Hall forced up a long shot. Dawkins barely missed blocking it, forcing Hall to shoot an airball. But Louisville center, Pervis Ellison, reacted quicker than Duke's big men and laid in the rebound for a three-point lead. Duke was down by only three points. Time was running out. Henderson missed a drive, and Louisville made two free throws to go up by five. Duke still couldn't make a jump shot but fought back desperately on the glass, scoring on rebounds by Bilas and Ferry, sandwiched around a missed Louisville free throw. Ferry's basket cut the lead to one. There were only three seconds left. Duke was forced to foul, and Louisville's Milt Wagner made two free throws. The final score: 72-69. "It never occurred to us that we would lose," Alarie says. "Never." It was a heart-rending coda. All five of the seniors graduated just a few weeks later. Still, while a win over Louisville would have been the perfect ending to the story, the legacy of the Class of '86 goes deeper than one game. These men committed to Duke at a time when the program was at its lowest ebb, guaranteed nothing but an opportunity to turn it around. They bought into Mike Krzyzewski's vision of excellence and helped make it come true, going through what Bilas calls an "extraordinary journey" from the basement to the top of the mountain. Duke won its first NCAA title five years later. Krzyzewski says he feels that "we would never have won in '91 without building on what the '86 team did. They defined the program. They became the example we've held up to every team since then, not just in how they played the game but in how they interacted with fans, how they handled class work. They laid the foundation." |

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor