The Nasher Museum of Art staff were facing COVID reality last summer. Their Ebony Patterson exhibit, “...while the dew is still on the roses…,” a rich, complex installation with art, video, patterned walls, and more than 12,000 individually placed flowers throughout the gallery, had to come down after having been open only ten days. It was impossible to predict when the doors would reopen. “We were devastated,” says Wendy Hower, director of engagement and marketing. “The building looks like it’s asleep.”

The museum staff tried to think of ways to wake it up and still serve the community, especially through artwork by artists from the diverse and underrepresented groups the museum showcases. Given the pandemic’s outsized effects on Black and Latinx populations, the blow felt doubly heartbreaking. Then Marshall Price, the Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger Curator of modern and contemporary art, opened his e-mail.

“It kind of fell in our laps,” he says. Artist and MacArthur grant-winner Carrie Mae Weems, a Black woman whose art is in the Nasher’s collection and who has collaborated before with the museum, had created an outdoor public art installation during a Syracuse residency, and she was spreading it out to museums in places like Philadelphia, Chicago, and Nashville, Tennessee. Did the Nasher want to participate?

“We felt like it was a really great opportunity,” Price says. “We kind of rolled up our sleeves and got to work.”

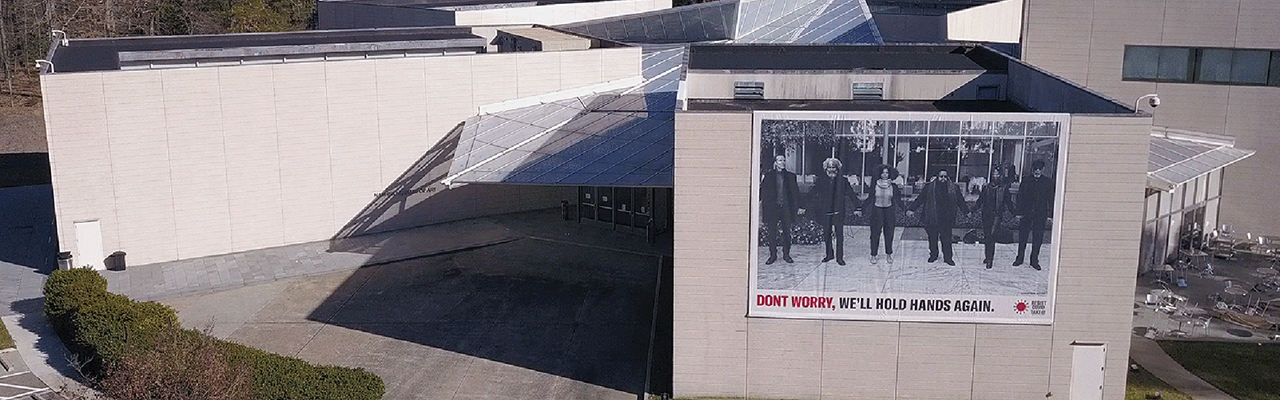

Weems’ work, called Resist Covid/Take 6!, exists completely outdoors, largely as public-service announcements and statements of encouragement about surviving COVID. “Don’t worry, we’ll hold hands again,” reads the caption of an enormous banner hanging on the outside of the Nasher, showing a row of people holding hands. Says one of a series of banners on Campus Drive lampposts: “Because of inequity, Black, Brown & Native people have been the most impacted by COVID-19. This must be changed!” Other banners and window clings thank frontline workers and remind people to practice social distancing. They show up on building sides and in windows all over Duke—on the Rubenstein Arts Center, on the gates to the (currently closed) Duke Gardens.

The signs show up all over Durham, too, from billboards to the windows of community partners like the American Dance Festival headquarters. Part of Weems’ design of the installation was that community collaboration. “It functions in that context just as much as a public-service announcement as art,” Price says. None of the posters have Duke or Nasher branding. The point is to get people talking about how to respond to COVID; how it’s affecting them and their community; how Black, brown, and native populations are being especially hard hit.

Buying billboards and printing up yard signs and posters isn’t cheap, and the Nasher partnered on both presentation and cost with Duke Arts and with Duke Health. Corrugated plastic signs, offered to residents free, now sprout in yards all over the Triangle, thanking workers and urging hand-washing.

And partners do more than hang signs, apply window clings, or distribute materials. ADF director Jodee Nimerichter sent out a call for submissions and ended up choosing a dozen dancers and companies to create dances in response to Weems’ messages. Each participant has then created a one-minute video, showing the dancer or group moving somewhere on campus or in Durham. The first video dropped in early February and showed dancer Tanu Sharma dancing in front of the Nasher; other videos showcase places like the downtown Durham bus station.

Dance is a perfect response to a pandemic that has had such a physical effect, Nimerichter says. The community is physically spread out now, yearning for touch and movement. “You come out moving the day you’re born,” so restrictions on movement seem to invite a response in dance, especially since dancers are themselves currently having to do most of their movement separately. “I think this installation is like a release of what’s been building up in their bodies,” Nimerichter says.

The Nasher has long collaborated with ADF, but when it started reaching out for partners, the response was so powerful that it made new friends as well. One new partner is the Duke Center for Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation. Associate director of engagement Jayne Ifekwunigwe says the center is gathering responses to the work. More than just the written-on-Post-its response museums often gather, an online questionnaire (on the Nasher website) will populate a database and allow Ifekwunigwe to analyze and interpret responses. “We invite visitors to speak their own truths” about how COVID has affected them and their communities, she says. “It was particularly important that we provided space for participants to name their losses and to express grief. We also wanted to encourage both hope and the possibility of transformation.”

Through images and response, through dance and yard signs, the installation sends that message of hope and transformation out into the community. “In my mind,” says Price, “these items are going out into the community and bringing this message with them.”

They go out and they spread, from person to person or in larger ways through the population. “They go out,” Price says, “kind of like a virus.”

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor