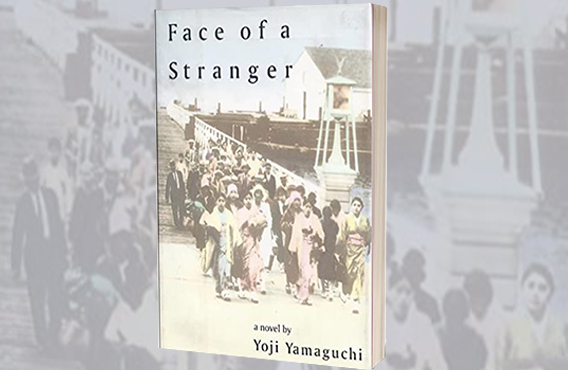

Face of a Stranger

By Yoji Yamaguchi '85. New York: HarperCollins. 202 pp. $18.

If asked to produce a sketch of an early twentieth-century immigrant's first view of America, most grade-schoolers will probably come up with a scene like this: midnight blue waves, a flotilla of lemon yellow ships decked with happy ruddy faces, all under the grinning eyes of a grass- green Statue of Liberty. The glorious fable of Ellis Island is, after all, what most history textbooks teach as the story about American immigration. Few of these textbooks, I suspect, would contain images of the treacherous rocky shores and dour, colorless barracks that confronted prospective citizens--mostly East Asians--entering the U.S. from its western portal, Angel Island, California.

Indeed, though it is sometimes called the Ellis Island of the West, this unremarkable plot of land situated at the mouth of the San Francisco Bay is no match for its eastern counterpart in either celebrity or photogenic appeal. An aerial shot of the island might be enhanced by the majestic Golden Gate Bridge nearby, but the photographer may have trouble blocking out another neighboring landmark, Alcatraz. Just a stone's throw away, that formal penal colony represents an ugly reminder that the Immigration Station on Angel Island functioned not only as a checkpoint, but also as a detention center, complete with metal cots, armed guards, and solitary confinement rooms--just like a prison.

The majority of those detained were men and women from China who, thanks to the Chinese Exclusion Acts (in effect from 1882 to 1943), were either denied entry into the States or let in only after they had gone through inordinately complicated and lengthy procedures. The Station also played host to a number of Japanese women who, like most of the female characters in Yoji Yamaguchi's Face of a Stranger, came to the United States as "picture brides" in remotely brokered marriages. For these immigrants, the less-than-heavenly scene they faced on Angel Island must have been a jarring contrast to the image of America they left home with--and left home for.

Face of a Stranger is all about "getting the wrong picture." Set in a Japanese immigrant community in early twentieth-century California, the novel tells the story of Kikue, who came to the U.S. with a snapshot of her handsome groom-to-be in hand, only to find that the marriage is a hoax and that she has been tricked into a life of prostitution. What's worse, as she becomes acquainted with other victims of Kato, the head of a massive gambling-prostitution ring and their "owner," she realizes that many of them have been lured to America by photographs of the same person: All have been duped by the likeness of a man who, more than likely, has himself been a dupe, and an unwitting pawn of Kato and his accomplices.

The novel opens with a chance encounter between the seasoned, resourceful Kikue and Arai Takashi, a down-and-out domestic servant who, she is certain, has supplied the face for that unlucky photograph. Years of indig-nity and a penchant for subterfuge urge her to give the hapless Takashi (dubbed "Master Face" by locals) a taste of his own medicine, even though she is already occupied with a plot to buy back her own freedom. With the help of her wily friend Shino (another alleged victim of "Master Face") and the comically simple farmer Kogoro, she sets into motion a baroque scheme of revenge that hinges, ironically, on the picture of a beautiful young woman named Hana.

Though Yamaguchi clearly thrives on intrigue and comedy, Face of a Stranger also offers a serious look at the "wrong pictures," the improbable illusions that early Japanese immigrants had of America. Twice in the novel, Takashi dreams that he has finally found the "good life" in a palatial home with a beautiful wife. Each time, his dream is invaded and turned into a nightmare by images from his daily life as a poorly paid house servant, one of many interchangeable and replaceable "Charlies" to his elderly white mistresses.

His dream bride, the irrepressible and often hilarious Hana, hopped onto a U.S.-bound ship on the promise that "a woman can be anything she wants to be over there." Once in "the land of the free," she finds herself locked up in solitary confinement at the Angel Island Immigration Station--her only "refuge," as it turns out, from Kato's henchmen and the Japanese-American missionaries who want to take her away to Montana and convert her to Christianity.

But why can't Kikue and company live the "American dream?" Yamaguchi tends to locate the seed of their misfortunes either in themselves or within the Japanese community. Kikue and her friend Shino are oppressed by Kato's gang and scorned by the middle-class, Christianized Japanese. In the end, Takashi is portrayed as a victim of his own greed and Kikue's ploy. White racism, except for the few brief episodes involving "Master Face" and his employers, is never treated at length or fully confronted. The most we get are a few passing and often oblique references that do not adequately address the exploitative economic conditions and exclusionary institutional practices faced by Japanese-Americans (such as a 1913 California state law which denied them land ownership).

Case in point: Halfway through the novel, Mrs. Inada, one of the Christian converts, laments that soon her brother and his fellow Issei (first generation Japanese-American) workers in an Alaskan fish cannery "would all be fired and left to fend for themselves in this foreign land" because they "had organized and were staging a general strike." This activist brother has never been mentioned before and, unfortunately, Yamaguchi never follows up on this story. Toward the end of the novel, Kikue goes on for several paragraphs about the hakujin's (white man's) power over the Japanese; but in the absence of any concrete examples of the racist attitudes she describes, the whole episode comes off contrived and unconvincing.

In light of the novel's reluctance to engage fully with racism, one might say that Face of a Stranger, despite its concerted effort to dispel the myth of "the land of the free," remains in its own way an idealized portrait of immigrant America.

Chia is a doctoral student in Duke's English department.

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor