|

Photos Duke Photography

by Elissa Lerner

Duke's new rules for allocating dorm rooms revolve around smaller living communities called "Houses," an idea borrowed from its residential past, with a few modern updates.

At the bottom of the last ridge separating the main part of West Campus from the Edens dormitories lies Keohane Quad. Its open U shape has finally closed with the first dorm on West to open since 2002. Though its exterior matches the Duke brick style of the rest of Keohane, the interior does anything but. Ample single bedrooms easily dwarf doubles in the older Gothic dorms on main West. Bay windows that could comfortably fit a twin extra-long mattress complement a staggering portion of the 150 rooms in the building. Enormous common rooms swathed in warm cherry wood tones branch off into demonstration-sized kitchens and study rooms equipped with floor-to-ceiling dryerase walls. And nestled beneath the structure is a new glass-encased atrium with doors that slide out to a plaza, some fuchsia arm chairs and plush sofas, and a 103-inch flat-screen television to complete the picture. This is K4—a dorm and an idea. Students already are raving about its amenities, but what they might not realize is that it's thoroughly a product of the university's new system for housing, which goes into effect this fall. In launching a new approach to residential life, it helps to have something concrete— like concrete. Like the addition of Blackwell and Randolph, which were shiny, new dorms when East Campus became a freshman campus, K4, in both design and spirit, will help ease the transition to the house system. The building is split neatly into two houses, one occupying the first two floors strucand the other the upper three. Each house has a separate entrance, leading into a sprawling two-story "great room" that is surrounded by bedrooms arranged like courtyard apartments, making it easy for students to see each other in passing. Some rooms are clustered in townhouse-style suites, with their own small living rooms. But while many universities are moving toward apartment-style dorm rooms with private amenities, K4's bathrooms and kitchens remain emphatically communal: All features of the building are meant to enhance interaction and community.

Courtesy Duke Housing, Dining, and Residence Life

Such an emphasis on smaller, tighter living arrangements is also meant to fix perceived housing inequalities. Antiquated dormitories on West and Central along with the expansion of Pratt's enrollment in 2004 have been exerting pressure on residence life for decades. Independent dents have been experiencing an increasingly different residential life from their colleagues and friends in fraternities and other selective living groups. Community— that intangible quality so carefully cultivated throughout the freshman-year experience on East—is often shattered upon the transition to sophomore year. By creating more cohesive living, Duke hopes to alleviate such tensions. If the idea works—that is, if Duke can successfully re-imagine its residential spaces—Duke can develop new communities and affinities throughout its large and diverse campus. But let's back up. In the old days, campus housing wasn't so complicated. Students were assigned to a dorm, and that dorm became their home for the next four years. Men primarily lived on West Campus; women were mostly housed as part of the Woman's College on East. But a growing student body and changing societal norms kept the assignment of on-campus housing in flux. The 1972 merger of the Woman's College with Trinity College required more change as the university experimented with how best to integrate men and women in its housing model. In the 1970s, Duke added housing on Central Campus. But even with the new space, overcrowding continued in the 1980s. Offices and common spaces in Hanes and Trent halls were converted into dorm rooms, and selective living groups were shuffled around campus to accommodate their growing numbers. Edens expanded, and new theme houses were created. Then came the campus-realigning decision to move all freshmen to East in 1994, which helped reduce pressure on dorms in West and Central. But it also required entire communities to relocate, effectively ending a residential model where students affiliated with multi-class houses and replacing it with a quad system. (Though ferociously criticized by some at the time, the East Campus concept actually didn't come out of a vacuum: All-freshman dorms have appeared and disappeared several times since 1960.) A smaller development came in 2002: In response to a report showing significant disparities in the racial composition of  In some ways, the house system is a logical progression from Duke's housing past. The plan will create small, cohesive living groups—"houses"—that allow sophomores, juniors, and seniors to root themselves in a stable community, much the way East dorms do for freshmen. Many of these living arrangements already exist: Fraternities and certain social and academic groups have been allocated blocks of rooms for decades where students can return year after year. The house model is an attempt to expand that approach to more students, more selective living groups, and more parts of campus. But it will disrupt some long-standing housing arrangements. Quad affiliation, in all of its imperfection, began emerging as long ago as 1968, when individual houses None of the changes has yet produced a flawless residential model. There has long been a perception, for example, that allowing students in fraternities and selective living groups (SLGs) to create neighborhood- like clusters alienates students who aren't affiliated with those groups. A housing report from as early as 1958 notes that "600 independent upperclassmen lived in unorganized anonymity" and laments "the disorder, the barbaric conditions of life." In 1994, Duke began allowing unaffiliated upperclassmen to form housing blocks and apply for particular dorms. But that hasn't erased the problem, says Steve Nowicki, dean and vice provost for undergraduate education.

"If a student is not in a social selective, he or she is treated like a hermit and a nomad," says Nowicki. "The student is a hermit, squeezed between frats and other selectives, and a nomad, because of the housing lottery every year." Housing allocations also have been criticized for favoring some SLGs, particularly fraternities, over others. For decades, sororities had no housing because of a Panhellenic Association pact that ensured all sororities would apply for housing together, or none would. As a result, Greek selective housing, which made up about half of the SLG housing on campus, was almost exclusively male. Responding to that disparity, the steering committee of the 2007 Campus Culture Initiative (CCI), a Duke officials heard the suggestion but, in a creative twist, they are flipping it on its head. The new housing system is an attempt to "take the best of what current SLGs have and benefit all students," says Joe Gonzalez, associate dean of Housing, Dining, and Residence Life (HDRL). "We can at least offer [independents] the opportunity to have more continuity." At the most basic level, the plan carves up the 3,912 beds on West and Central into eighty-two self-contained groups of thirty to 100 students. These "houses" don't always comprise a freestanding physical space; in some cases, they are defined Instead, houses will offer rising juniors and seniors a "right of return," meaning they'll be guaranteed a bed in the house if they want to come back for another year. "Our hope is that [students] will want to stay in their house," says Gonzalez. "Ideally, within five to seven years, there should be upperclass houses with meaning, like East Campus houses." By reconfiguring all of its upperclass beds into houses, Duke also will be able to incorporate a wider range of SLGs. For the first time in Duke's history, all of the university's sororities will have official housing sections. And when the houses open this fall, there will be three SLGs based on cultural affinity—Latino, Asian, and black— also a first for Duke. Though such additions to campus culture are being realized through housing, they are actually pieces of a larger, holistic effort to improve campus life. The residence model and its new living groups are part of a plethora of updates to dining and social spaces, including the upcoming renovations of the West Campus Union and Page Auditorium. But they also already anticipate increased foot traffic through the new K4 atrium and plaza, and a reinvigorated Central. Contrary to some student perceptions, the new house model did not pop up overnight. Its long incubation began with discussions in 2007, following the CCI report's controversial recommendation to abolish housing privileges for SLGs. In 2009, Duke formed a committee of undergraduate students, administrators, and faculty members to work out the logistics for the new model. Key among these early student contributors were members of the now-defunct Campus Council, a leadership body committed to residential government that has since been merged into Duke Student Government. By February 2011, the committee was far enough along to start sharing elements of the plan with the rest of the campus through ongoing town-hall meetings. But it wasn't until this past fall when the selection process was imminent that many students took notice.  And when they did, some were not pleased. Throughout September and October, The Chronicle's online comments lit up with anger and confusion about the house system. Some students panned the concept as simply an imitation of residential models at Yale and other prestigious universities, where students often stay in the same dorm all their years on campus. Others questioned how unaffiliated students would be assigned to houses and whether existing SLGs would be moved. Tensions peaked on a Wednesday evening in late October when SLGs and unaffiliated houses received their future campus locations. Although officially billed as a lottery, the process was, out of necessity, much more structured. "It's random with constraints," Nowicki explained in the days leading up to the event. The eighty-two houses created in the new model are not of uniform size. Small- and medium-sized houses, accommodating around forty students, exist in far greater proportion on Central Campus and in Craven and Edens. Because the overwhelming majority of SLGs have forty members or fewer—and because sororities applied for housing for the first time— some clustering of SLGs in those areas was inevitable, Gonzalez says. In the final assignment, out of the twenty-seven houses on Central, twenty-one will be SLGs, fifteen of which are Greek. Only six will be unaffiliated. The process also involved a delicate balance between student desires and institutional objectives. While Duke wanted an equitable process, it also was concerned about maintaining a representative mix of races, genders, and affiliations in residential communities. The overrepresentation of white students on West Campus—one of the factors that led Duke to require all sophomores to live on West—has persisted. In the fall of 2006, West Campus housed 81 percent of Duke's white students, but only 76 percent of Latino students, 73 percent of Asian students, and 58 percent of African-American students. Consequently, administrators were concerned about assignments that would have too big an influence on residential culture. The problem manifested in finding space for Duke's nine sororities, which wanted houses for portions of their chapters but preferred to stay together on one campus. Honoring that request allowed only one viable option: Central. Panhellenic Association president Jenny Ngo, a senior, says many members weren't overjoyed with the choice, as Central is often perceived by students as remote and lacking character. But they are ready to make it work. "Since our number one commitment was to be on one campus together, we committed to Central," she says.

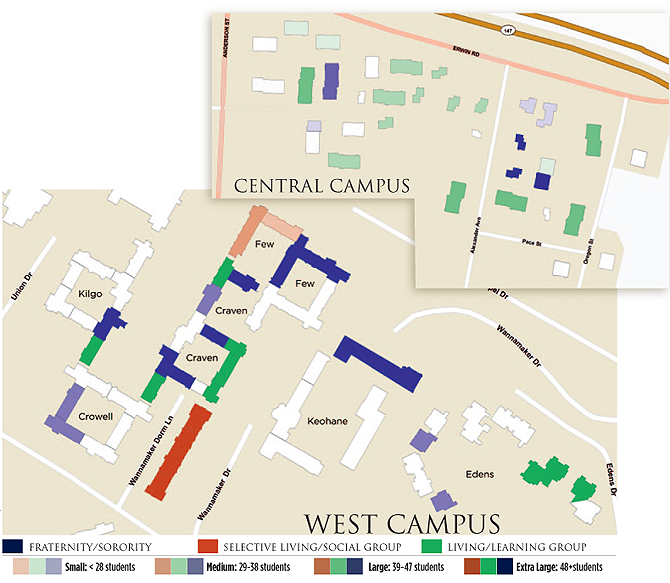

Mixing it up: New house assignments will change the distribution of Greek and selective living groups on West and Central campuses.

Central already has undergone some substantial renovations—including a new restaurant, clearer fencing and signage, a new grocery store, and a few refurbished apartments—and administrators say its reputation is changing. "Central has really been spiffed up," says Donna Lisker, associate dean for undergraduate education. "What we're finding is that groups that have been assigned to Central love it— they don't want to come back [to West Campus]. "However, Ngo wants to see continued improvements. She hopes to align with other SLGs on Central to bring a proposal to administrators to improve lighting, increase security patrols, and install card-swipe access in common areas on Central. She also points out the need for more recreation and dining options in the area. "There are only two eateries [on Central] right now, and on Sundays, when all chapters meet, there will be 1,000 women on one campus," she says. "I think having more sophomores on Central is going to bring some energy and life that it has lacked over the years," says Gonzalez. "I believe many of the students who join houses here will think they got the better assignment. And there's going to be a presence of SLGs on Central at a level that really hasn't happened before. That's going to change the dynamic of Central Campus also. " The inclusion of culturally based SLGs is another new dynamic that bears watching. The three houses— organized by the Black Student Alliance, Mi Gente (Duke's Latino student association), and the Asian Students Association— are open to members of any race. Ultimately, the number of beds allotted for cultural student houses is quite small, but they have nonetheless raised some concerns about whether students of color will selfsegregate into communities along racial lines. Writing in The Chronicle, columnist Rui Dai, a junior, argued that allowing culturally defined living groups "represents a setback for racial and ethnic integration…. It is perfectly acceptable to want to live with our friends, but the racial part of that decision should not become part of the institutional model." Nowicki expects the houses to be "outward looking." "They should be a beacon, not a refuge, for a language, or culture, or region of a group," he says. Lisker points to the robust African and African-American Studies major, majors surrounding Asian and Asian-American topics, and study-abroad programs like DukeEngage as examples of successful programs that attract students of all races. "I do think it can work," she says. "None of us could see any justification in not at least trying it. Other schools have it and with great success, so it's worth the effort." Junior Derek Mong, president of the Asian Students Association (ASA), says he heard some backlash about self-segregation when ASA debated applying for a house. But the decision to proceed was "pretty simple," he says. "Within ASA, there's always been talk of the lack of Asian-American space on campus, and we thought that a space specifically devoted to Asian cultural issues was definitely necessary, especially given how Duke's undergraduate demographic has been changing so much." (Asian students now comprise approximately one-quarter of the undergraduate population, and ASA will guide the largest of the cultural houses with approximately forty-five beds.) Several cultural groups opted not to apply for houses. When board members of Diya, Duke's South Asian cultural group, discussed the idea, no one could come up with positive reasons for creating a South Asian-themed house. The Muslim Students Association also briefly considered applying for a house, "but we thought it was too isolating," says senior Nadir Ijaz, president of MSA. But experiences vary significantly among Duke's cultural groups, making blanket assessments impossible. Senior Nana Asante, two-term president of the Black Student Alliance, says African-American students see clear value in a cultural living group, a desire articulated as early as the Allen Building takeover of 1969. "It was more than just waking up in the morning and deciding to establish a black culture house. We've been doing research on living groups across the country and thinking critically about the impact and potential of this house, not to mention answering to issues of self-segregation," she says. "By no means is the black community only inclusive of those with black skin color, especially when we think about the very diverse African diaspora." Still, "there's only so much we can do," she says. "It's the responsibility of all of us to take the initiative to make us more aware global citizens. I'm sure it will be different to get members who are not members of the black community to take interest. But we're not interested in pressuring people. The onus also lies on individuals themselves and how we choose to immerse ourselves." Given the fact that historically many students of color have elected to live on Central, Asante finds it somewhat ironic that the Black Cultural Living Group ended up on the outskirts of Central. "I can't say it's particularly ideal or what we wanted," she says. "But we're grateful for this opportunity to make the most of it and to fulfill the mission. We're black students; it's what we do anyway. I've learned to appreciate that." As with every aspect of the house system, it will be a few years before any kind of success can be evaluated. It remains to be seen how SLGs will fit into their new spaces, and whether unaffiliated nomads will embrace the house model's communitarian spirit. But administrators are confident that students will come around—or return— to the concept of house living. "The pushback has only been in the past couple of months, and it's just anxiety about something new," says Lisker. "My expectation is that this will be like East Campus. Before it was implemented, people were very upset by this idea and outraged that President [Nannerl O.] Keohane would suggest it. And then within a year, it was the best thing that ever happened to the university." And the inevitable fact about students is that they are just passing through. Within two years, most of the students disrupted by the reallocation of houses will have graduated, and few will know any system but the new one. Perhaps this system really will stabilize residential life for upperclassmen the way East Campus has for freshmen. Perhaps Central will continue to develop as a social hub. But if those things don't happen, history teaches us to count on one thing: Duke will alter the plan. As Nowicki noted in a letter to parents explaining the house model, "While our buildings may be made of stone, our ideas about campus life are not." Stay tuned. |

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor