Tonight, take a moment to gaze toward the heavens and salute the moon. After all, it was fifty years ago this month that Apollo 11 launched from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center and Neil Armstrong took his “small step.”

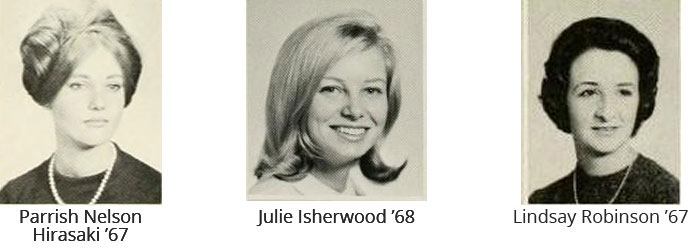

And, on the team it took to pull off such a historic feat were three Duke alumnae. Parrish Nelson Hirasaki ’67, Julie Isherwood ’68, and Lindsay Robinson ’67 all worked on the Apollo program. And by their telling, they had the time of their lives doing it.

Photos courtesy of Duke University Archives

“Our families thought we were rock stars,” says Hirasaki, with delight in her voice. “Even though I was part of a large group, they would tell people the astronauts couldn’t have gone to the moon without me.”

The women worked for TRW, an aerospace contractor for NASA, and were based in Houston. Hirasaki did the calculations for the command module’s heat shield, a critical piece in protecting the astronauts as the module re-entered Earth’s atmosphere. Isherwood was a kind of trouble-shooter; she worked in the trajectory analysis division, helping to generate the abort parameters, and later, on lunar ascent and descent. Or in simple terms for non-rocket scientists: “If astronauts saw our numbers, they were in real big trouble,” she says. Robinson worked with computer simulations for the electrical power systems on the lunar, command, and service modules.

Their accomplishments happened, of course, when there were few women in their fields, and in their courses of study at Duke. Initially, Hirasaki was a math major, struggling with her liberal arts requirements, and aiming to be a schoolteacher, because “God forbid something happened to my husband, I could work,” she says, explaining the era’s mindset.

Her path changed when, at the beginning of her sophomore year, her roommate wanted to drop out of Duke. Hirasaki and a group of friends tried to intervene by taking her to the university’s counseling services. While there they were tested to see what careers they should seek.

“It turned out the counselor had attended four schools, so she thought it was a good idea for my friend to transfer to another college,” she says. “But she looked at my scores and suggested I go into mechanical engineering.”

What at the time seemed just a good way to get out of a language requirement, turned out to be a perfect fit for her. “I was in my element. It would have been a shame if I had never found it.”

Isherwood was a math major who’d decided she wanted to work with computers, whatever they were. “My father was an attorney and I thought I wanted to be one too, but my father’s partner talked me out of it.”

Duke didn’t have much of a math department and no computer science, but one day on a bulletin board, she saw a flyer advertising a free seminar teaching basic coding on the men’s campus. Attendees got all the computer time they wanted. At first, more than 100 students were learning; little by little, the class whittled down to just seven. In those early days, they used long paper tapes to code—punch cards came in her sophomore year.

Thomas Gallie, professor of mathematics (and later, director of the computer science program and leader of the Triangle Universities Computation Center), saw her talent and set her up for a consultant job at Duke Hospital, where she helped develop a program that scanned for cancer.

Robinson came to Duke with advanced placement in both liberal arts and science, but chose engineering for the discipline and because she feared she might have to support her aging family. While women in engineering usually made half of what men did, the pay was still much more than she’d make with a liberal arts degree. In electrical engineering, she found energy flow, loop equations, circuit design, and computers to be right up her alley.

By her senior year, Isherwood had lots of job interviews, including with Bell Labs. “A guy told me, ‘Whatever you do, don’t work for the space program. Everything you do after will be boring.’” That led her to TRW. But after talking to them, she found she didn’t meet their qualifications. She decided to ask the representative for advice on a coding problem she was having. They talked it through, and in the end, decided to hire her anyway. “I think they liked my problem-solving,” she says.

A year earlier, Hirasaki, who was vice president of the Duke engineering school student government, had garnered three offers from the space program. “I chose Houston because that’s where the action was,” she says. Robinson joined her.

Indeed, it was where the action was both at work and socially. Everyone lived in adults-only complexes across the street from where they worked. “It was like being in college without having to study,” says Hirasaki.

She met her husband, John, and married him six months before the Apollo 11 flight; he was the NASA mechanical engineer who was in the quarantine trailer with the astronauts. John introduced Isherwood to her husband, at a motorcross race.

Hirasaki worked with all the manned missions; during Apollo 13 did calculations to bring the astronauts back, a critical role. Later, she worked in the energy industry for thirty years but went back to NASA after the 2003 shuttle crash because of the heat shield problems. She retired in 2009 and now is a painter, living with her husband in Culver City, California. “I chose math over art before college, and while painting is a nice hobby, it’s a good thing I went with math,” she says, laughing.

Isherwood quit the computer field, she says, because she discovered she didn’t like authority. She and her husband started a plumbing business; Isherwood became one of the first licensed women plumbers in Arizona. She then segued into general contracting and later took over her mother’s real-estate business in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where she grew up.

After the moon walk, Robinson accepted a job at the Applied Physics Lab in Maryland, working on Navy related projects. Later, she left engineering and moved into a little-known field that focused on psychology—how people learn and how to design training that works. She retired from that field in 2011. Based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, she continues exploring human capabilities, now in energy healing. Robinson was delighted when a teacher used electrical meters to show that healers transmit energy. “Here I am, back with energy flows,” she says.

All three women are enjoying the attention the Apollo landing anniversary has brought to their work. Yet it’s not really the past for them. Says Isherwood, “I’ve talked about it all my life. He was right—the rest was a letdown.”

Hirasaki agrees. “It didn’t sneak up on me. I had been thinking about it.”

After all, most nights, there’s a reminder right in the sky.

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor