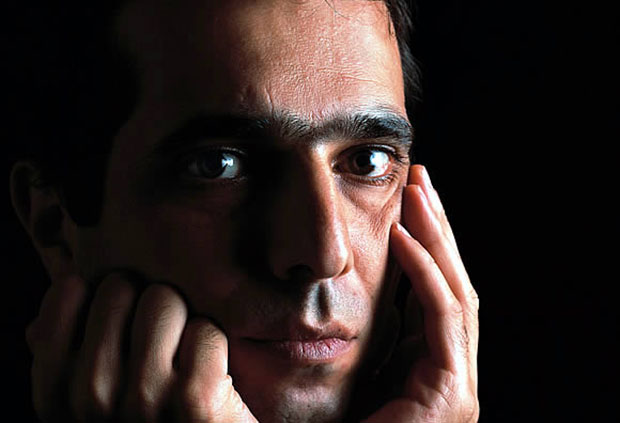

Yektan Turkyilmaz was reveling in scholarly satisfaction.Having spent two months poring over archival collections--an interlude critical to wrapping up his dissertation work--he was sitting in an airport lounge, finishing off a cigarette and talking with three friends who had come to see him off. The airport is just a few miles outside Yerevan, Armenia's capital. Turkyilmaz was looking forward to the two-hour, late-night flight to Istanbul. There he would continue his research as a sixth-year Duke graduate student in cultural anthropology. The single-runway airport is called Zvartnots, which has at least two meanings: "celestial angels" or "vigilant forces." In the past two weeks, he had become somewhat vigilant, somewhat uneasy. He had noticed several men clustered just outside his apartment building, seemingly at all hours of the day and night. And he had learned that a number of Armenian acquaintances had been questioned about his work in the country.

He walked through the security checkpoint, then through passport control, where the officer appeared strangely alarmed in his presence and quickly stamped his passport. After taking a couple of steps toward the gate, he was rushed by seven or eight security agents. Moments later, he was in handcuffs, his pockets emptied, his luggage seized. He was told that he wouldn't be seeing a lawyer anytime soon. The friends who saw him off at the airport were instructed to forget about him, to avoid discussing his arrest. He was thrown in jail at the headquarters of the National Security Service, still referred to as the KGB, and held under tight security. What did Yektan Turkyilmaz do for his summer? He became a subject of news accounts all over the world. He helped set in motion a scholarly network that transcends national and disciplinary boundaries. And he became a symbol of ethnic rivalries that have simmered for decades. To his Armenian inquisitors, even his name was a maddening, and menacing, study in contradictions. "Turkyilmaz," in Turkish, means "indomitable Turk"; "Yektan," in Kurdish, means unique. Back in the days of the Ottoman Empire, Turks had committed atrocities against Armenians that, in the view of most scholars, amounted to genocide. Since the founding of the Turkish Republic in 1923, the government has clamped down on Kurdish aspirations for cultural and political autonomy. Turkyilmaz--a citizen of Turkey who is of Kurdish origin and who is hardly likely to tow the Turkish party line--had been researching the period of the genocide. He had earned some acclaim as the first Turkish national to gain access to Armenia's National Archives. The Armenian KGB arrested him on June 17, having targeted him as a spy. "All scholars are spies," one of the investigators told him. All of his research materials, including some 20,000 images saved on more than thirty CDs, were confiscated, along with a backup set of CDs that he had left with a friend. He was asked to prove that he had permission to reproduce every one of those images, which were scrutinized, one by one, to see whether they revealed state secrets. He was questioned about his politics, dissertation topic, motivations for learning the Armenian language, and knowledge of the Turkish military and intelligence communities. None of that revealed anything of interest to investigators, he says. And so the espionage suspicions evaporated. But after being held without bail for more than a month, he was charged, on July 21, with attempting to remove prohibited articles from the country, specifically, 108 books and pamphlets dating from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries. They had all been purchased openly and legally, he says, at flea markets and secondhand booksellers within sight of the presidential palace. Most of them related to the activities of Armenian nationalist parties in the Ottoman Empire and so, he says, would contribute to his doctoral studies. He adds that he has for years collected Armenian books and recordings, and that his collection has been tapped by other Turkish students for their research. The claim of innocence carried no weight with prosecutors. They argued that he had violated an article of the Armenian Criminal Code that prohibits transporting drugs, ammunition, or nuclear weapons out of the country. Also barred is the export of certain "raw materials or cultural values" without permission from the Ministry of Culture. Turkyilmaz said that he had never heard of the law. Reportedly, this was the first time that it had been applied to a person carrying books. The person who wrote the book on Armenia--specifically, a two-volume history--was among Turkyilmaz's prominent defenders. Richard Hovannisian, who holds a chair in Armenian history at the University of California at Los Angeles, is the founder of the Society for Armenian Studies. On hearing of Turkyilmaz's case, he sent messages to the Armenian president and the foreign ministry, flew to Armenia, and met with the lead prosecutor to attest to the character of the young scholar and plead for his speedy release. He says, "I've met Yektan, and I have a very high opinion of him as an objective scholar, one who tries to understand what occurred in the very controversial and confusing history of modern Turkey, who does not necessarily accept the state's narrative of events and the mythology that has been created in Turkey, and who is willing to challenge it. He is among those who are asking the very fundamental question, If there were two-million Armenians living in Turkey in 1915 and there are none here now, what happened to them? They did not simply get up and walk away. They were eliminated." Hovannisian says he told the prosecutor, "Look, if this man were really intending to smuggle books, he certainly would not have put them on a plane headed for Istanbul, which would have been suspicious for anyone. He would have found a circuitous route to have gotten those books out of the country." All he received in reply was "something of a semi-bureaucratic response, a message that we are, after all, the defenders of the law, even though on a personal level we might sympathize with this young man," he says. "It was a lot of double-talk." In late August, after two months in prison, Turkyilmaz was given a two-year suspended prison sentence and set free. The court had convicted him of two counts of smuggling. But it chose not to impose additional prison time. State prosecutors had cited his partial acknowledgment of his guilt and cooperation with investigators. "I now want to concentrate on my doctoral dissertation," he told the journalists present at the trial. "I was, I am, and I will remain a friend of the Armenians." Even before that public statement of friendship, Turkyilmaz would have been a strange candidate for a Turkish spy. He is a member of Turkey's Kurdish minority, which has a history of being marginalized, and worse: While the Kurds make up more than 20 percent of the population of Turkey, the government has shut down Kurdish political parties, banned the Kurdish language, imprisoned advocates of separatism, and systematically withheld economic resources from the Kurdish region. It also has violently fought a Kurdish nationalist movement, displacing an estimated million villagers in the process. Until a few decades ago, the government wouldn't even acknowledge a Kurdish minority, instead applying labels like "Mountain Turks." Turkyilmaz grew up in what he calls "a multicultural environment" in southeastern Turkey. From an early age, he was sensitive to historical tensions that would later contribute to his project as a scholar. He's drawn to questions related to geography, maps, and borders; he's curious about how different ethnic groups conceive their homelands, sometimes through competing claims. "Armenians became Armenians through these strong experiences. So did Kurds. So did Turks. The history that I want to write is not just about history. It's about today. I want to understand why we are as we are today, and why we have these problems." "I'm not particularly interested in Armenians or Kurds or Turks," he says. "I'm more interested generally in ethnic conflict. Why do people decide that they should kill each other? Why do people want to maintain conflicts rather than settling the issues? What does the formation of a state tell us about ethnic groups? What is a state, anyway? And is it possible to find a common identity beyond ethnic boundaries?" His dissertation is titled "Imagining 'Turkey,' Creating a Nation: The Politics of Geography and State Formation in Eastern Anatolia, 1908-1938."

Turkyilmaz identifies himself as among a new generation of scholars in Turkey who reject an official "Turkish" view of history. In May, he had told Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty, "Interestingly, people in Turkey believe that Armenia's archives are closed, especially for Turkish citizens. That is not true. Here I am easily working with them." Turkey, he said on the radio, has been slow to recognize the mass killings and deportations of Armenians, in the years during and following World War I, as genocide. That ugly episode allowed Turkey to take control of the eastern region of the country, known as Anatolia, the geographic focus of his dissertation. "Sadly, young people in Turkey know nothing about the subject," he says. "All they know are nationalist things written in school textbooks. And because they lack that knowledge, they believe that the Armenians plot bad things against their country." On the other side of the border--and of history--Armenia is afflicted with "this strange mixture of new Armenian nationalism," in his words, "along with the Soviet tradition that is still very influential in Armenian political institutions." His scholarly interests and his initial welcome in Armenia defied a Turkish stereotype about Armenia; his later arrest and imprisonment reinforced it. "Turkish and Armenian history have been written from polar-opposite perspectives for several generations now," says Charles Kurzman, associate professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Kurzman is a member of Turkyilmaz's dissertation committee, taught him in a seminar, and employed him as a research assistant. The young scholar, Kurzman says, has unusual qualifications in researching a topic that crosses cultures. "Very few scholars have been able to work in both languages, because Turkish is not widely taught in Armenia, and the Armenian language is not widely taught in Turkey. Yektan is one of the few scholars who can work in both languages, and I believe he's the only scholar of his generation who can work in Armenian, Kurdish, and Turkish. That allows him access to materials and perspectives that people have not previously put together. So he is a great future hope for this field." Whether or not mutual understanding is achieved in the scholarly world, in the sphere of Turkish officialdom, the issue of Armenian genocide continues to be sensitive. It's especially sensitive at the moment, as Turkey looks to enter the European Union. As The Economist observed in reporting on Turkyilmaz's case, if Turkey is to join the E.U., it may have to acknowledge, and allow free discussion of, the genocide. But the signs of openness are, at best, mixed. Kurzman observes that there are struggles within the Turkish government, and between the government and the military. Even different wings of Turkey's Islamist movement disagree on issues such as promoting democracy and pursuing membership in the European Union. Orhan Pamuk, Turkey's most acclaimed living novelist, is facing up to three years in jail on charges of "denigrating the Turkish identity" after telling a Swiss newspaper last February that "30,000 Kurds were killed here, one million Armenians as well." In late September, a court in Istanbul blocked an academic conference, "Ottoman Armenians During the Demise of the Empire: Responsible Scholarship and Issues of Democracy." The court banned the conference from the two universities that had co-sponsored it, pending information on the qualifications of the speakers. But there was rampant criticism of the court's decision, by both the media and government officials. Finally, a third university agreed to hold the event, which had already been postponed in May after the justice minister accused its organizers of treason. Participants were greeted by demonstrators shouting "Treason will not go unpunished" and "This is Turkey, love it or leave it." But the conference was a "transformative experience for most of the participants," according to Ayse Gul Altinay Ph.D. '01, an assistant professor of anthropology and cultural studies at Sabanci University in Istanbul. "After two intense days of twelve to thirteen hours each, a serious taboo has been broken," she says, referring to the long-stymied discussion of Armenian genocide. Turkish officials have long accepted that many Armenians were killed on Turkish soil beginning in 1915. But that happened, they have insisted, during a time of civil strife in the declining days of the Ottoman Empire that claimed even more Turkish Muslim lives. Turkey closed its border and cut diplomatic ties with Armenia in 1993--two years after Armenia achieved independence from the old Soviet Union--to protest against Armenian occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh, a territory that Stalin had placed in Soviet Azerbaijan. "I know how fraught these questions of nationalism, history, and Armenian genocide are in this part of the world," says Duke cultural-anthropology professor Orin Starn, who is Turkyilmaz's dissertation adviser. "I think Yetkan fully realized the potential dangers of doing research in Armenia. Anthropologists sometimes tend to be confused with spies anyway, because we're the people who are there asking uncomfortable questions, writing things down in our notebooks. And in Yektan's case, taking pictures of documents." When Starn was doing field work in Peru, he was accused of being a spy for the U.S. government. "A lot of anthropologists now work in dangerous places, on topics that are politically charged," he says. "You have the stereotype of the anthropologist as this person going off to work in some so-called exotic culture and writing about religious symbolism or social structure. And that was what anthropology was fifty years ago. But anthropologists have become very interested in questions of social movement, political change, ethnic nationalism, war, memory, genocide. Anthropology is a field that's become more engaged in political issues, and I think that's a good thing. It shows that we're doing and studying things that matter, that have real-world stakes and consequences. But it often means being in places that are not safe. And Yektan was in one of those places." When news broke of his arrest, scholars, and politicians, rallied in support of Turkyilmaz. Duke president Richard H. Brodhead noted, in a letter to President Robert Kocharian of Armenia, that Turkyilmaz is uniquely qualified "to help illuminate this critical historical period." Turkyilmaz's circumstances also caught the attention of former Senator Bob Dole, whose wife, Senator Elizabeth Hanford Dole '58, Hon. '00, served as a Duke trustee. Bob Dole has had a longstanding affinity for Armenia: After he was severely wounded in World War II, he had seven corrective surgeries from a Chicago-based army surgeon of Armenian origin. He would later credit the surgeon, Hampar Kilikian--a survivor of the Armenian genocide--with persuading him "to make the most of what I had." Dole learned about the case through his counsel, Marion Watkins '96, J.D. '99, who was absorbing e-mail messages from Duke sources. In his letter to President Kocharian, Dole said that to detain Turkyilmaz "on grounds as dubious as these calls into question Armenia's commitment to democracy in the first place." Dole urged the president to ask the country's legislature "to examine this strange law"--the ban on exporting a book of cultural value--"which, if not unique in the world, is certainly unique in the community of free nations." Speaking for various communities of scholars, organizations like International PEN, which is a worldwide association of writers, the Human Rights Action Network of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the Society for Armenian Studies argued on behalf of Turkyilmaz. In a typical sentiment, the Middle East Studies Association of North America said the case violated the notion that "scholarship, free exchange of ideas, and international collegiality can help lessen political tensions between states and increase mutual respect and understanding amongst peoples."

One scholar who advocated tirelessly for Turkyilmaz was Altinay, the Istanbul-based professor who, like Turkyilmaz, completed her Duke dissertation under Starn's supervision. She has known Turkyilaz for more than five years and says that his research "promises to build important academic and human bridges between areas of scholarship divided by politically troubled borders, languages, and disciplines." In late July, Altinay entered Armenia on a tourist visa; she was met at Yerevan's airport by the same friends who had seen off Turkyilmaz when he was arrested. Her next meeting, with the imprisoned scholar, was more freighted and frightening. "They first put me in a room that looked like an interrogation room," she recalls. "There was a desk and three chairs, all of which were nailed to the floor. Nothing could be moved. The door was covered with thick leather from the inside, which might have been for sound isolation. Yektan came into the room with a KGB agent, who accompanied us during the whole visit. He asked Yektan to sit behind the desk, while I sat in front of the desk." Altinay says she tried to provide him with information about the international attention on the case, and "to reassure him that this nightmare would end soon." She recalls, "He looked serious, calm, and strong." As he was being led away, "I told him that we would soon be meeting under very different circumstances. I believed--or wanted to believe--that this would indeed be the case. But he seemed more pessimistic. I could see the deep worry in his eyes." On her return to Istanbul, she helped organize the Committee for Solidarity with Yektan Turkyilmaz, which included prominent writers, journalists, and intellectuals. They crafted an open letter to President Kocharian and, in less than twenty-four hours, collected 100 signatures. The petition was impressive in its international reach--especially so, Altinay observes, because it was the first time that Turkish and Armenian scholars had come together on this scale. Even as he was targeted by the national-security apparatus, Turkyilmaz continued to receive support from other sectors of Armenia. In a radio interview, the director of the National Archives called the trial a mistake. One of Turkyilmaz's cellmates burst into laughter, he recalls, on learning that Turkyilmaz's imprisonment hinged on a dispute over book exports. His situation just didn't fit into the convenient categories that define official Armenia's view of the world--or that define scholars who are citizens of Turkey. "My first thought was that the right hand and the left hand in the Armenian government were working at cross purposes," says UNC's Kurzman, who maintained a "Free Yektan" website throughout the episode. "You have a move by the National Archives to grant Yektan permission to perform his research there, clearly an attempt to further the cause of scholarship and to gain good publicity. On the other hand, you have people there who are very suspicious of outsiders telling their story for them. And it appears that some of those people--many of them, I would guess, Soviet trained--saw only trouble in having a scholar from Turkey look at their documents and leave the country with information that they considered central to their national identity." The early suspicions that he must have been spying for Turkey constitute "the big irony there," Kurzman says. "That of all the people from Turkey who might come look at their documents, he's among the most sympathetic. So I think it backfired on them. Once they had him, they couldn't just let him go without losing face. But they couldn't keep him either, because of the international outcry and because it was counterproductive to their own cause, which is to have Armenian historical claims validated." Starn, Turkyilmaz's dissertation adviser, flew to Yerevan, the capital, to observe the trial. It was, in Starn's view, only a show trial. The state prosecutor hinged his argument, he says, on the theory that Turkyilmaz had acquired too many books for any authentic student to absorb; Turkyilmaz's intent, so the argument went, must have been smuggling. At trial's end, as the judge was reaching his decision, the prosecutor blithely walked out of the courtroom. That display of nonchalance, Starn says, was an indication that the verdict was preordained. "I think this falls within the larger context of this deep historical mistrust between Armenia and Turkey, this feeling in Armenia that they have suffered at the hands of the Turks, that they've been massacred by the Turks, that Turkey took over 90 percent of their territory, and therefore Turkey only means bad things for Armenia and Armenians. The very fact of a Turk, albeit one of Kurdish descent, being in Armenia, photographing documents in the archives, buying books about Armenian history, culture, and politics, making a lot of Armenian friends, was something unusual. Yektan is a real pioneer in this sense. I think that inevitably made him a target of suspicion." He may have been a target of suspicion there, but Turkyilmaz sees Armenia as a target of scholarly opportunity. "I will definitely go back" to Armenia, he says, though he thinks he has compiled enough material to finish his dissertation. He left having lost 20 pounds in prison, but with his books and CDs back in his possession. Hovannisian, the UCLA expert on Armenia, says Turkyilmaz's case illustrates how a nation like Armenia--finding itself alongside the historically hostile neighbors of Turkey and Azerbaijan--can be in a perpetual mode of insecurity and crisis. That circumstance can feed a fervent patriotism that perceives threats everywhere, he says. At the same time, Turkey has been slow to deal with the burden of historical memory. "We in the United States have our own difficulties facing the skeletons in our closet," says Hovannisian. "It was a very long time until we acknowledged the mistreatment of the Native American population and the evils of slavery. So it takes maturity to be able to face your history." "There is hope that civil society is opening up in Turkey, and maybe it will spill over into Armenia," he says. "The Turkish scholars today who are talking about these issues are not doing it for any love of Armenians. They're saying that we in Turkey can't really know who we are, can't really face our future, unless we deal with our past." |

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor