A group of Duke and other scientists have found a tiny fossilized tooth that identifies the smallest monkey in the world’s fossil record. They have named the monkey and added it to the fossil record, which is cool. But what’s really remarkable is the effort behind the finding of that tooth and the vast hole in our understanding that the little fossil begins to fill.

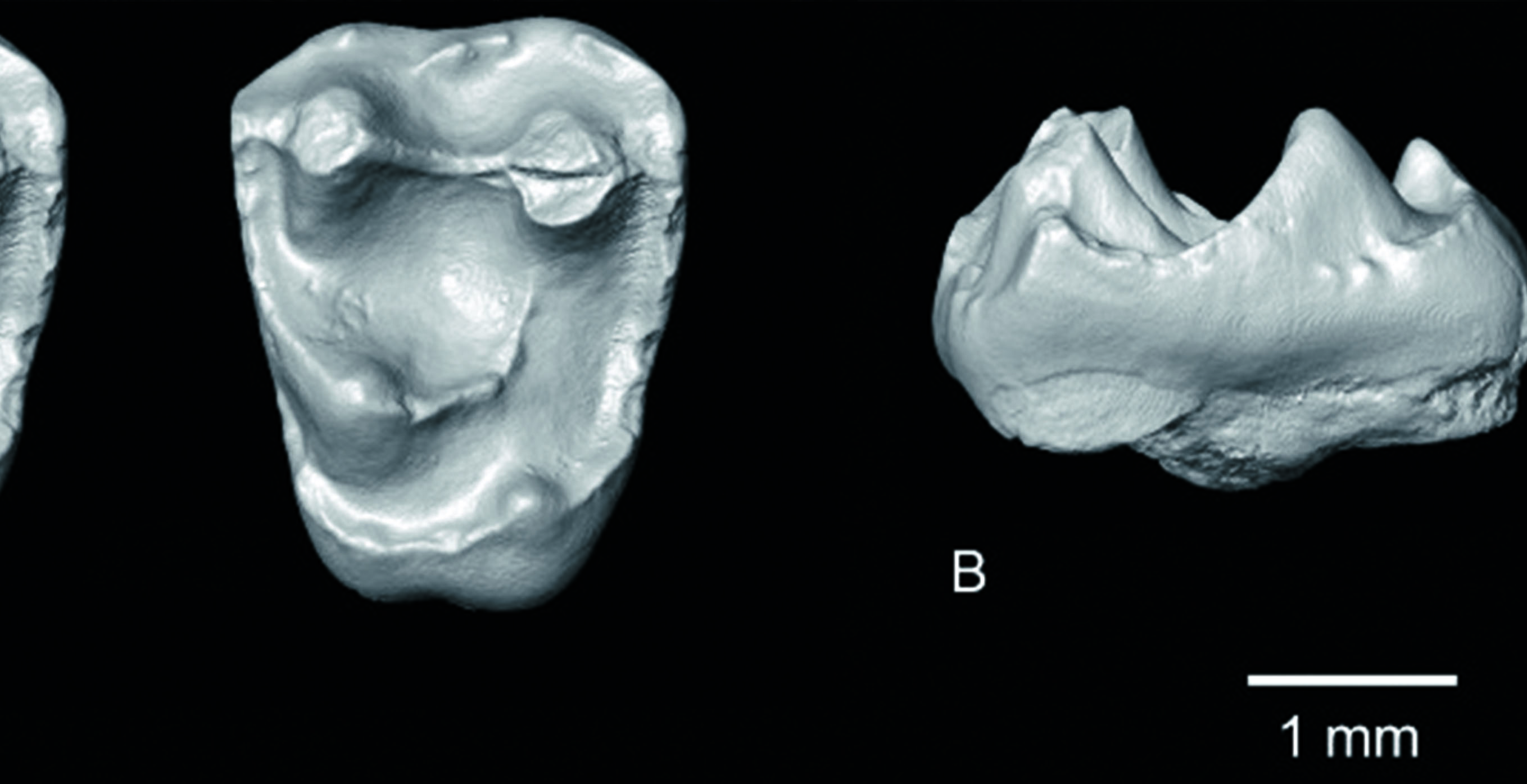

The fossil is a tooth, and if you had a hundred of them, they would fit in a teaspoon. The monkey that used to come attached to that tooth was just a wee bit larger than today’s smallest monkey, the pygmy marmoset, which weighs in at three ounces, about the weight of a cupcake. The name of the new fossil monkey is Parvimico materdei, which means “tiny monkey from the Mother of God River,” which describes the monkey and the area of Peru in which it was found. Parvimico was probably a bit larger than the pygmy marmoset—so think maybe one of those giant cupcakes with all the frosting.

They’ve figured all that out from one tooth?

Yep. “What can you say about this animal?” asks lead author Richard Kay, professor of evolutionary anthropology. “Well, actually a little bit about its size, because teeth are a good indicator of that.” Hence its comparison to the pygmy marmoset, though the two are not closely related. “And a little bit about its diet, because [teeth are] the business end of what you’re eating.” In this case, given the shape of the bumps and ridges on that tooth, probably fruits, insects, and saps.

Little Parvimico materdei is a big deal because it adds a little drop of information into an enormous void in the fossil record. “Although we’ve been documenting the biodiversity of vertebrates in the tropics today,” Kay says, “we just don’t have very much in the way of fossils to look at the biodiversity in deeper time.” South American monkeys appear to have arrived from Africa by raft around 30 to 40 million years ago. (Yes, raft; probably on big floating piles of organic detritus, possibly large enough to have supported trees.)

There are primate fossils—again, usually nothing more than a tooth or two—from around 30 million years ago, and then some more from around 13 or 14 million years ago. That’s a gap of close to 20 million years, which is a lot of empty space. “Our fossil falls into that gap at about 17, 18 million years ago,” Kay says. Which gives a glimpse of how New World monkeys were evolving, filling ecological niches over time.

One reason for that hole in the fossil record is the difficulty of getting to where the fossils are. The problem is the Amazon basin is flat and has been for some time, so the strata from tens of millions of years ago, where fossils would be, are deep in the ground. That has meant a lot of looking for fossils in dryer, more mountainous areas where it’s easy to look for them, rather than where they might more likely be: “It’s like the drunk looking for his keys under the lamppost,” Kay says. “You go where there are fossils, and you hope for the best.”

Fortunately, geological maps, often made during the search for fossil fuels, show where, as plates have collided, that Amazonian plain has bunched up like a rug, creating folds of mountains, bringing some of those old strata closer to the surface. “Then look for a place where there’s one of those folds, flattened down by erosion, with a river cutting right through the middle of it,” Kay says. That’s what they found along the Rio Alto Madre de Dios in southeastern Peru, and they started looking for fossils.

Don’t think people with whisk brooms and little hammers; not when you’re looking for tiny fragments and teeth among the clay strata of the jungly Amazon. “You grab a bunch of rock from your outcrop and you bring it back to a sandbar, and you put it in detergent with water, and the clay breaks down,” Kay says. “You scoop that stuff into screens and you wash it in the river. Then you’ve got your screen-washed concentrate.” That reduces what you’ve got by about 90 percent.

“Then you handpick it, looking for fossils.” Not a quick job. “To find that tooth,” Kay says, “we had to go through a ton of sediment. It’s frustrating, because you could spend a whole season, and you wouldn’t find anything.” And even if you do, “you might not know you’ve recovered it until a couple years later when you finally get through picking the screen wash.”

So Parvimico materdei was a win, and Kay is hopeful for more. After another summer of digging, “we just shipped more than 300 kilograms of washed sediment” to the paleontology lab of his collaborator at Universidad Nacional de Piura, Jean-Noel Martinez. Kay says Martinez has good students.

Good thing. Parvimico is a tiny monkey, Kay says, “but boy, that’s a big job.”

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor