In 1932, toddler Charles A. Lindbergh Jr. was kidnapped and held for ransom in a case that made international headlines as “the Crime of the Century.” Lindbergh, the first-born son of aviation hero Charles A. Lindbergh and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was later found dead. A Bronx carpenter named Bruno Hauptmann—who claimed innocence until the end—was eventually convicted and put to death for the crime.

But many people remained convinced that Hauptmann had not acted alone. The child had been abducted from his second-story bedroom and carried down a ladder, a task seemingly unmanageable for just one person to accomplish. And then there was the shadowy figure dubbed “Cemetery John,” who had intercepted the ransom payment during a graveyard rendezvous, and who bore no resemblance to Hauptmann.

Eugene C. Zorn Jr. lived in the same New York borough as Hauptmann. Over time, Zorn became convinced that, as a teenager, he had unwittingly overheard a conversation plotting the Lindbergh kidnapping—and that his former neighbor, John Knoll, might be the man known as Cemetery John. On Christmas Eve 2006, as he lay dying, he asked his son, Robert, to uncover the truth about who kidnapped and killed Charles A. Lindbergh Jr.

"I kept thinking that I might find evidence which disproved my father's theory. But I kept finding more and more evidence that proved him right."

In Cemetery John: The Undiscovered Mastermind of the Lindbergh Kidnapping, Robert Zorn has fulfilled his promise. During three years of research, Zorn amassed a preponderance of evidence to reach a stunning conclusion: Three men were involved in the kidnapping conspiracy, including Hauptmann and Knoll, who had befriended Eugene Zorn in the early 1930s. What’s more, Knoll, whose physical description matches that of the never-identified Cemetery John figure in the case right down to a deformed left thumb, intentionally and systematically provided the teenager with clues about the crime.

“I kept thinking that I might find evidence which disproved my father’s theory,” says Zorn, whose quest became all-consuming. “But I kept finding more and more evidence that proved him right.”

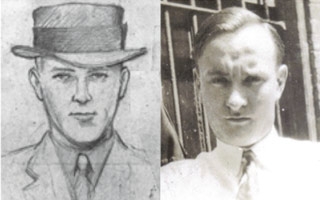

Mounting evidence: A 1932 police sketch of "Cemetery John," the kidnapper who collected a $50,000 ransom in a Bronx cemetery, left, and a picture of John Knoll, who left clues about the kidnapping for Zorn to discover. [Courtesy Robert Zorn]

Zorn reached out to dozens of experts to help him understand and interpret new evidence he uncovered through interviews and archival research. The experts used twenty-first-century criminal investigative techniques—forensic pathology and linguistics, handwriting analysis, psychiatry, and psychology—to re-examine existing evidence. The group included retired FBI special agent John Douglas, who pioneered the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit; former New Jersey Gov. Brendan T. Byrne, who had long believed that Hauptmann had accomplices; and forensic anthropologist Kathy Reichs, producer of the television show Bones and the model for its main character. After studying the evidence, even a niece of John Knoll’s told Zorn, “Uncle John should have done the right thing and turned himself in.”

Cemetery John has prompted renewed public and media interest in the Lindbergh kidnapping. PBS’s Nova will air a special featuring Zorn’s story in early 2013, and a Hollywood film producer has already approached him about a possible movie treatment.

Zorn sometimes imagines confronting John Knoll with the proof of his role as the criminal mastermind of the case. But that confrontation only happens in Zorn’s imagination. Two months after Eugene Zorn first shared his suspicions about the Lindbergh kidnapping with his son, John Knoll died after falling off a ladder and hitting his head.

Share your comments

Have an account?

Sign in to commentNo Account?

Email the editor